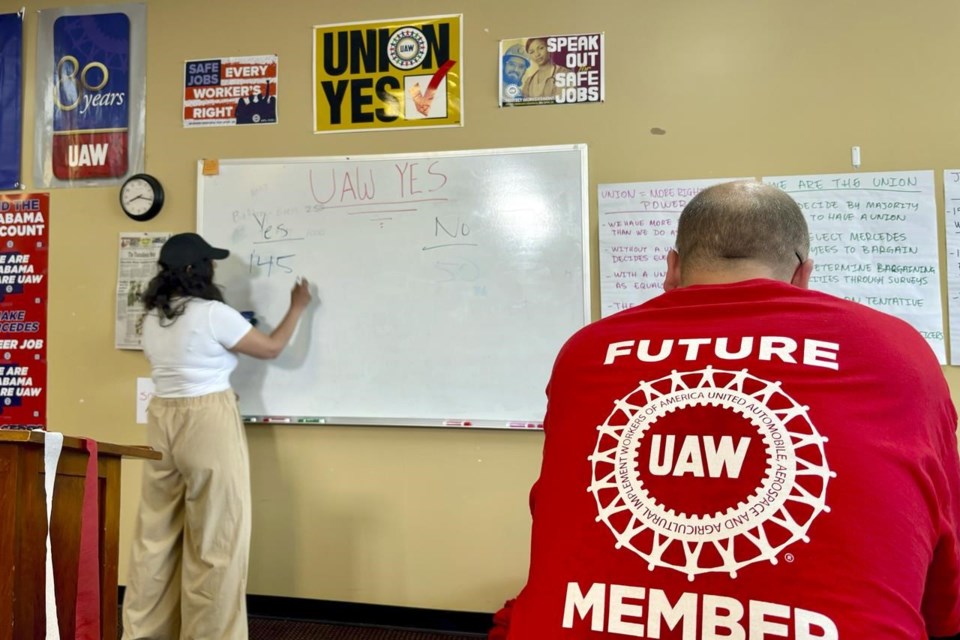

TUSCALOOSA, Ala. (AP) — Workers at two Mercedes-Benz factories near Tuscaloosa, Alabama, voted overwhelmingly against joining the United Auto Workers on Friday, a setback in the union’s drive to organize plants in the historically nonunion South.

The workers voted 56% against the union, according to tallies released by the National Labor Relations Board, which ran the election.

The NLRB's final tally showed a vote of 2,642 to 2,045 workers against the union. A total of 5,075 voters were eligible to vote at an auto assembly plant and a battery factory in and near Vance, Alabama, not far from Tuscaloosa, the board said.

The NLRB said both sides have five business days to file objections to the election. The union must wait a year before seeking another vote.

The loss slows the UAW's effort to organize 150,000 workers at more than a dozen nonunion auto factories largely in the South.

The voting at the two Mercedes factories comes a month after the UAW scored a breakthrough victory at Volkswagen’s assembly factory in Chattanooga, Tennessee. In that election, VW workers voted overwhelmingly to join the UAW, drawn by the prospect of substantially higher wages and other benefits.

The UAW had little success before then recruiting at nonunion auto plants in the South, where workers have been much less drawn to organized labor than in the traditional union strongholds of Michigan and other industrial Midwest states.

A victory at the Mercedes plants would have represented a huge plum for the union, which has long struggled to overcome the enticements that Southern states have bestowed on foreign automakers, including tax breaks, lower labor costs and a nonunion workforce.

Some Southern governors have warned that voting for union membership could, over time, cost workers their jobs because of the higher costs that the auto companies would have to bear.

Yet the UAW was campaigning from a stronger position than in the past. Besides its victory in Chattanooga, it achieved generous new contracts last fall after striking against Detroit Big 3 automakers: General Motors, Stellantis and Ford. Workers there gained 33% pay raises in contracts that will expire in 2028.

Top-scale production workers at GM, who now earn about $36 an hour, will make nearly $43 an hour by the end of their contract, plus annual profit-sharing checks. Mercedes has increased top production worker pay to $34 an hour, a move that some workers say was intended to fend off the UAW.

Shortly after workers ratified the Detroit contract, UAW President Shawn Fain announced a drive to organize about 150,000 workers at more than a dozen nonunion plants, mostly run by foreign-based automakers with plants in Southern states. In addition, Tesla’s U.S. factories, which are nonunion, are in the UAW’s sights.

It turns out that the union had a tougher time in Alabama than in Tennessee, where the UAW narrowly lost two previous votes and was familiar with workers at the factory. The UAW has accused Mercedes of using management and anti-union consultants to try to intimidate workers.

In a statement Thursday, Mercedes denied interfering with or retaliating against workers who were pursuing union representation. The company has said it looked forward to all workers having a chance to cast a secret ballot “as well as having access to the information necessary to make an informed choice” on unionization.

If the union had won, it would have been a huge momentum booster for the UAW as it seeks to organize more factories, said Marick Masters, a professor emeritus at Wayne State University’s business school who has long studied the union.

Interviewed before the results were in, Masters said he expected that even a loss would not stop the UAW leadership, which he said would likely explore legal options. That could include arguing to the National Labor Relations Board that Mercedes’ actions made it impossible for union representation to receive a fair election.

Though the loss is a setback for the UAW, Masters suggested it would not deal a fatal blow to its membership drive. The union will have to analyze why it couldn’t garner more than 50% of the vote, given its statement that a “supermajority” of workers signed cards authorizing an election, Masters said. The UAW wouldn’t say what percentage or how many workers signed up.

The loss could lead workers at other nonunion plants to wonder why Mercedes employees voted against the union. But Masters said he doesn’t think it will slow down the union.

“I would expect them to intensify their efforts, to try to be more thoughtful and see what went wrong,” he said.

If the UAW eventually manages to organize nonunion plants at Hyundai, Kia, Nissan, Toyota and Honda with contracts similar to those it won in Detroit, more automakers would have to bear the same labor costs. That potentially could lead the automakers to raise vehicle prices.

Some workers at Mercedes say the company treated them poorly until the UAW’s organizing drive began, then offered pay raises, eliminated a lower tier of pay for new hires and even replaced the plant CEO.

__

Krisher reported from Detroit.

Tom Krisher And Kim Chandler, The Associated Press