Before Brentwood mall moved in, before houses sprouted up, before the streets were even paved, the Brentwood neighbourhood was a place of woodlands and creeks, according to former resident Geraldine Knibb.

“It’s just unbelievable what they’ve done in that area,” she says of the neighbourhood today, adding the SkyTrain is right where she used to turn up Alpha Avenue to get to her home. “It seems like it’s up in the heavens.”

Nowadays, Knibb lives in White Rock, where she retired with her husband. But in 1946, her father gave her husband an acre of property in the area between Willingdon and Alpha avenues, right where Brentwood Town Centre is today. Back then, there were only three houses in the area between Alpha and Beta avenues, she says – the red shack originally on her property, the house her husband built, and her sister’s home nearby. Otherwise, there was no one around, she says.

“It was all bush,” she adds.

The shack was originally owned by a First World War veteran, a bachelor, who willed it to her father, according to Knibb.

“In those days, there were all kinds of old bachelors living in that area,” she says, adding they all had an acre of land.

In 1959, developers came knocking. Brentwood Mall opened two years later.

“In those days, they didn’t tell you what they were going to develop. They just knocked on our door one night and said, ‘We don’t want your house, we just want your property,’” she says. “We were able to live in the house to ’60. By this time, the bulldozer was starting to come down, so we decided to move the house.”

The family had the house loaded on a truck and transported to Duthie Avenue and Broadway, she says. The red shack was moved to Spring Avenue and Hastings Street, and her sister’s home was moved to Grandview Highway.

Her husband was involved in developing the area. He worked as a carpenter building houses in Willingdon Heights, as well as homes and apartment buildings in Vancouver, Knibb says.

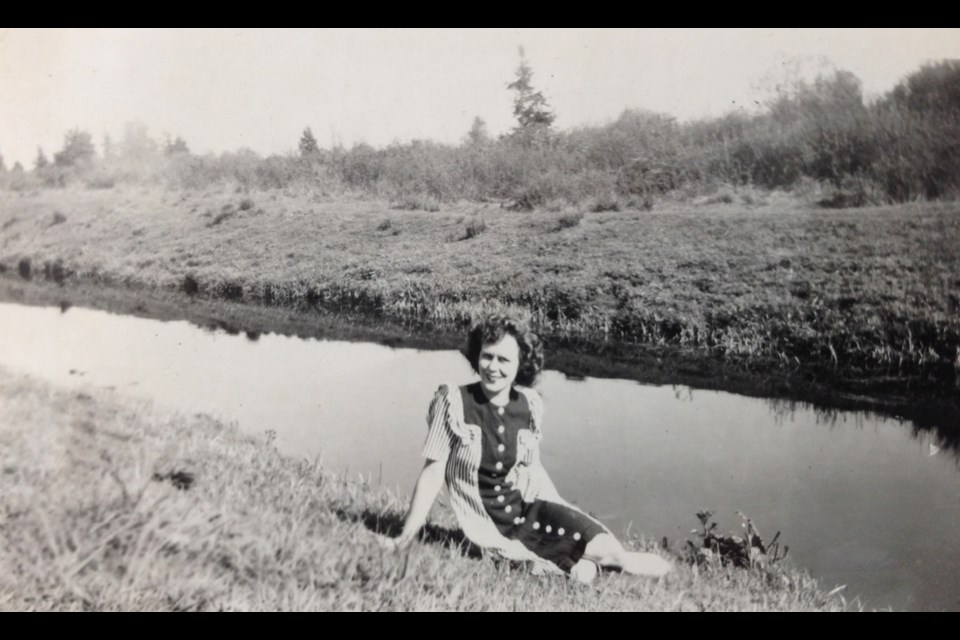

Knibb first moved to Burnaby with her parents when she was five. Born over the border in Washington, she first lived in Vancouver, and moved alongside Still Creek in 1929, she says.

“We had a little yellow house, a two-room house, and my mother and father and five children,” she says. “Our little house was right on the creek between Willingdon Avenue and the Burnaby Lake trestle.”

The children hauled water from the creek on Willingdon Avenue up to the house so their mother could wash clothes, she says.

We had quite a time down on our creek,” she adds.

But living beside a waterway wasn’t all fun and games.

“I was there when we had the flood. The creek flooded up, and it came up as high as the train tracks, and Burnaby Lake, and over as far as Douglas Road,” Knibb says. “In fact, there was a Chinese gardener who lived over on Douglas Road, and the people that got off the Burnaby Lake tram, he had to row the ones that lived down on Grandview Highway.”

The family had to move after five years because the area wasn’t good for their health, she says.

“I had a sister that died at the age of 13, and a sister that had a bad heart, and the doctor said we had to move,” Knibb says. “It was damp down there, it was all peat moss.”

Burnaby planned to dredge Still Creek at the time, so they traded her father for an acre of land on Dawson Street and Willingdon Avenue, according to Knibb.

Today, the Keg and Costco sit on the property her family owned on Dawson Street, and a creek that divided the property is gone, she says.

But it’s not just the homes and waterways and woods that Knibb misses from her childhood – it’s the people, she says.

“I find it really sad because there’s not one soul… I just love to talk about when we lived down on the creek, and there’s not one soul living that I can laugh and say, ‘remember the good days,’” she says. “Nobody’s left.”