Sachi Komura Rummel was only eight years old when the United States dropped a nuclear bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945.

She had been playing with her friends in the schoolyard just moments before the blast, which occurred less than four kilometres away from where she was standing.

Today, the 79-year-old Canadian citizen and Squamish resident belongs to the “hibakusha” club, a group of about 183,000 atomic bomb survivors who are still alive. To her knowledge, she is as healthy as can be.

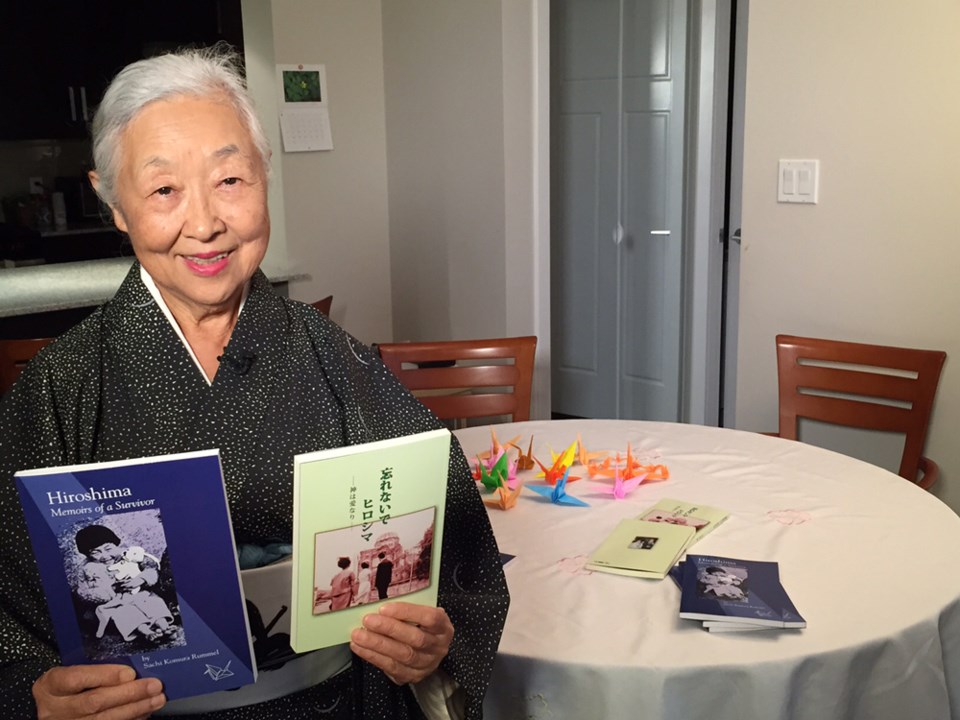

But it was only in 2011, after the nuclear power plant accident in Fukushima, Japan that Rummel broke her silence about surviving the attack. She went on to publish Hiroshima: Memoirs of a Survivor, and travel to local schools and libraries to share her story.

The NOW caught up with Rummel recently to ask her about the harrowing experience and why she waited so long to come forward.

For anyone interested in knowing more, she’ll be doing a talk at the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre on Saturday, Nov. 26, starting at 2 p.m.

Take me back to Aug. 6 1945, where were you and what were you doing moments before the bomb went off?

Around that time, I don’t think there was any summer holidays, so we were at school. I was eight years old and playing on the school grounds. It was summertime, so there’s a big tree. We are playing under the shade of the tree. Suddenly, (there was a) strong flash I saw. Then after that, all in front of me, was whitish because all of the dust from the blowing of the bomb. We were 3.5 kilometres away from the ground zero, but 3.5 is not too far away. We were sort of running around screaming and crying, then the teacher said, “Come into the classroom.” The classroom, the window side, was broken, so it was dangerous. We sat down in the chair and the teacher calmed down everyone. The school arranged (for us) to go home by an elder student leader, like a Grade 5 or 6 (student). Instead of going through the normal road, we went through the mountain. (We) had black rain. The rain has a kind of tar and oil (feel), with radiation included. I was wearing a whitish blouse that spotted with black. This black never came out. It remained there. … It was 4,000 degrees Celsius. Can you imagine? Instantly, everything is near dead, charcoaled. Dead bodies, animals, humans.

Where was your family at the time?

My house was in Takasu. My (mom) was there, but my father was working downtown, close to ground zero. My aunt – her husband went to war – she had a little boy. She felt in danger, so she moved to our place. She went to volunteer downtown (that day). She never returned. Just 10 days after the bomb, the first day after the Second World War finished, my dad died. With my aunt, we had hope she may come back. My father was ill and stayed in bed. It was more emotional to see him dying instead of my aunt, who we still had a hope she may come back.

My father really loved me. I was a spoiled child, and I really liked him. In that time, there was no coffin or cemetery, so they just dug holes in the park. There were hundreds and hundreds of people burning every day. My father was carried in a kind of stretcher and then brought to one of the parks. That time, I screamed, “Don’t burn my father.” It was a disaster. You can’t believe me how bad (it was).

You kept your survivor story quiet until 2011, the year there was a nuclear power plant accident in Fukushima, Japan. Why is that?

I didn’t really talk about it. I didn’t intentionally not talk about it, but also, not many people asked. In daily life, we don’t say those things, unless the subject comes up. When my grandchildren were born, I thought I better write it down. Radiation is so dangerous, so I wanted to tell people how terrible it is and how difficult it is to live after that. … I have a fear one day I will have a cancer sickness, because many people had cancer, thyroid and leukemia. I’m afraid. On the other side, I thought if I have cancer, that’s OK. In one way, I’m (fearful). In one way, it’s my fate and I have to accept it. … Many people are victims, surviving with some kind of fear, scar or sickness. Some of them are normal, but you never know. Last week, my husband came back from Japan and he heard many people have cancer and have died, but government doesn’t say; just be quiet and don’t announce. I just want to let people know how it affects humans.

What do you think of today’s nuclear situation?

Science (has) developed more and more dangerous (weapons). Now, they’re almost a thousand times bigger than Hiroshima. Everyone should demolish all the nuclear weapons. I want our future to be without nuclear weapons and nuclear war. I can’t say nuclear energy, because we need (it). It’s very difficult to completely eliminate (them), but individually, we should think what’s the best way to stop (them) and have peace. (It’s why) I like to talk to young adults and students. Even Grade 2s. They quietly listen. One little boy said, “I’m trembling.” I think because this is a true story and I am talking about my experience. I think it impacts people more than just reading novels or someone’s book. … I’m like a grandmother storyteller. I visit different schools. I ask them (what) they think. This society depends on the young people now.