An SFU researcher who has spent a lot of time studying ways to stop seniors from getting hurt during falls is ready to put his skills to work protecting hockey players from concussions, thanks to research grants announced last month.

Stephen Robinovitch, lead researcher for the Technology for Injury Prevention in Seniors (TIPS) program at SFU’s Burnaby campus, was among a bumper crop of SFU researchers awarded 2014 Discovery grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

In all, 82 Simon Fraser faculty earned the grants totalling $13 million – $6 million more than last year.

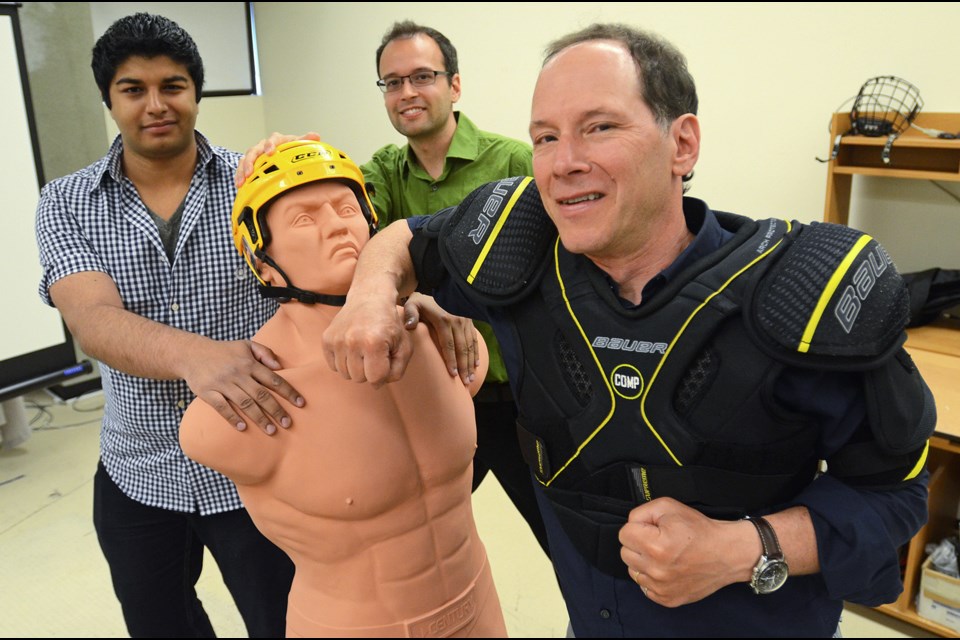

Robinovitch will use his $32,000 to fund the first year of a new research project aimed at improving the design of hockey pads and boards to prevent head injuries during ice-hockey collisions.

It may seem like a big switch from his work with injury prevention in seniors, where the medical engineer studies what causes seniors to fall and develops and tests engineering interventions like hip pads and shock-absorbent flooring, but Robinovitch – a Canucks fan – said there are some “interesting parallels.”

For starters, both hockey players and seniors are at high risk for injury, he said.

And he and his fellow researchers will use some of the same techniques they’ve used to analyze seniors’ falls – video capture and wearable sensors – and use them to study “impact events” on the ice.

The hockey study will feature both on-ice and lab components.

The on-ice portion will see researchers partner with the SFU men’s hockey team and two elite youth teams.

Using video and sensors roughly the size and shape of a domino attached to players’ helmets, researchers will track the typical scenarios that lead to head impacts.

Those will then be recreated and analyzed in the department of biomedical physiology and kinesiology’s Injury Prevention and Mobility Laboratory.

What sets Robinovitch’s study apart is that it will focus, not on improving helmets, but on improving shoulder pads, elbow pads and boards to reduce head injuries.

At least 40 per cent of hockey concussions are related to shoulder-to-head contact, Robinovitch said, yet shoulder and elbow pads continue to be designed like armour with hard shells and ridges that concentrate force.

Another 30 per cent of concussions are related to head-to-board contact, another area that has gotten little attention.

“We are looking at two things that people have talked about but no one has done any work on before,” Robinovitch told the NOW.

So far, buy-in from stakeholders, like hockey players and league administrators, has been enthusiastic, according to Robinovitch, but he said that likely wouldn’t have been the case if his study had focused on the evils of hitting.

“We weren’t coming in with an agenda on how the game should be played,” he said.

That being said, Robinovitch isn’t ruling out that his study’s findings could help improve hitting rules as well as hockey pads and boards.

He expects the project to take about five years and will apply for multi-year funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council next year.

In the meantime, he’s found that his new research topic is an easier sell at parties.

“It’s become the go-to cocktail party conversation for me,” he said.