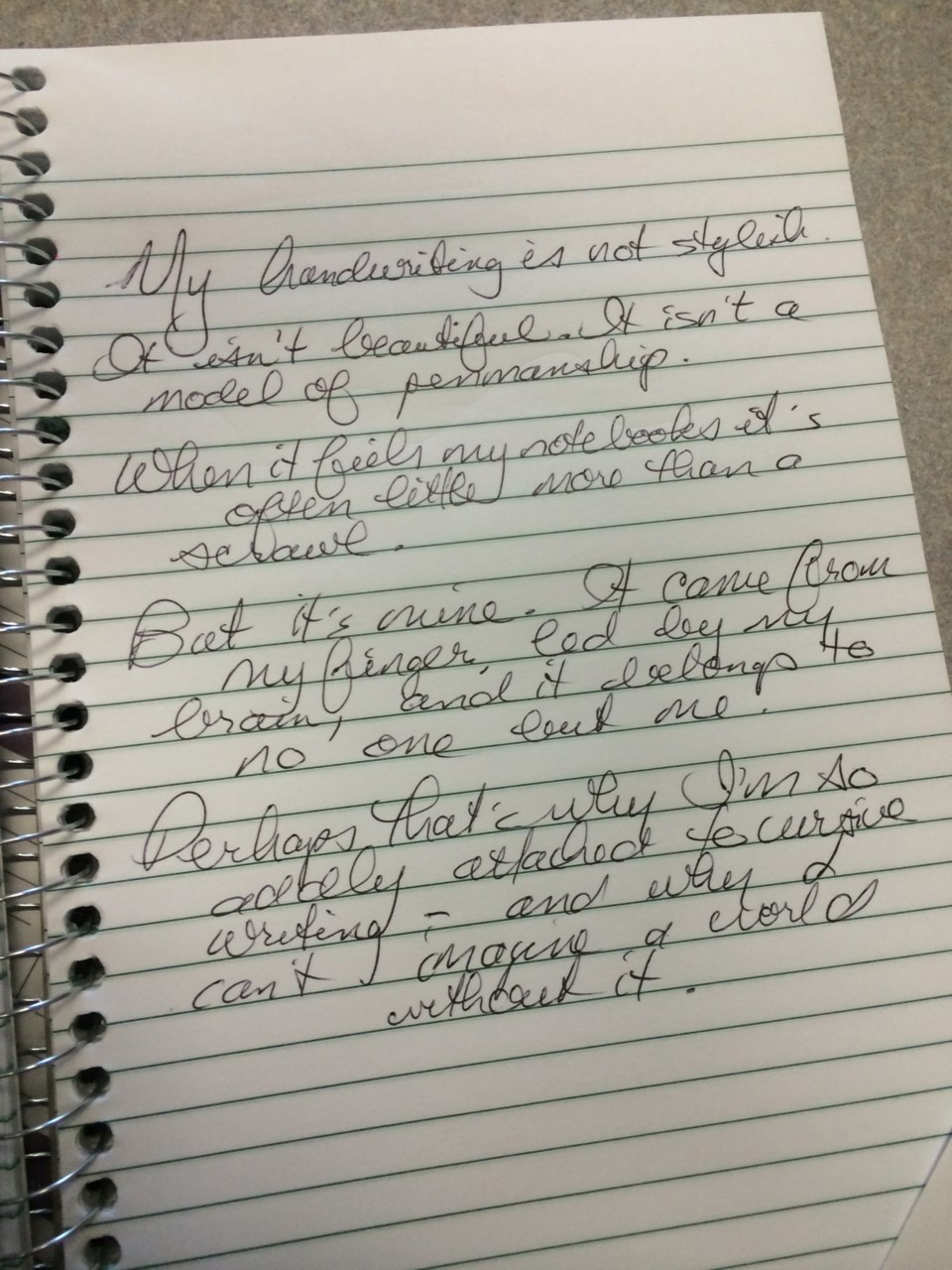

My handwriting is not beautiful.

It’s not stylish. It isn’t a model of perfect penmanship, with just-so descenders and ascenders reaching precise lengths and each letter curving gracefully into the next.

When it fills my notebooks it’s often little more than a scrawl.

But it’s mine. It came from my fingers, led by my brain, and it belongs to no one but me.

Perhaps that’s why I’m so oddly attached to cursive writing – and why I can’t imagine a world without it.

I got to thinking about the power of cursive the other day when I came across this great New York Times piece (posted on Twitter by @JuanitaNg).

The piece argues, quite soundly, that cursive is no longer a necessary skill and that it’s no longer essential to teach it to our children.

Think about that for a moment.

Imagine that in my lifetime, a skill I worked so hard to master in Mrs. Nishman’s Grade 4 class and Mr. Carroll’s Grade 5 class, a skill that has been in many ways the essence of how I have communicated with the world for 35 years, a skill that has all my life been taken for granted as something all people should know how to do, may simply become obsolete.

Gulp.

In many ways, the logic is unassailable. Cursive used to make simple, practical sense because it was faster than printing; when your pen doesn’t come off the paper, you can make more letters faster. End of story.

On that front, it’s obvious that typing simply makes more sense. When it comes to speed, efficiency and clarity, keyboarding is the clear winner. In a world where technology is all around us, it’s hard to deny its usefulness.

And there are other benefits for kids, too. Those who don’t have early fine motor skills and would struggle to learn cursive writing can share their thoughts with greater speed and accuracy than ever before. When they’re not stuck trying to master the basic mechanics of letter formation, they can move on to the meat of what they’re actually trying to say – both the substance of the message and the style of its delivery. Which could in fact mean that, paradoxically, in eliminating the need for cursive writing we are freeing our children to become better writers.

On the flip side, there are many studies that argue the benefits of cursive writing, and I can’t dismiss those lightly. Its usefulness in the development of fine motor control and, more broadly, its influence on cognitive development, cannot be overlooked. Handwriting activates your brain differently than typing does; it integrates the tactile experience of your hand holding a pen to the visual experience of forming and recognizing letters in a way that simply hitting keys on a keyboard can never do.

Which is part of the reason why I cling to the idea that cursive shouldn’t disappear. But only part.

The bigger part, for me, is somewhat less tangible.

For me, the value of cursive lies in the fact that handwriting is so utterly and absolutely personal. Not just in the sense of developing a recognizable signature for legal purposes – although that’s a useful thing, I wouldn’t suggest that cursive is the only way to create a “signature” – but in the sense that it is an activity that engages every part of our being.

When my brain and my fingers are so essentially connected, I simply think differently than I do when I’m at a keyboard. There’s a reason why more of my favourite writing – the creative, fiction writing I like to do in my spare time – began life with pen and paper. Connecting with a pen simply draws from a different well than typing on a keyboard, pulling thoughts and ideas from a place deep within.

Typing detaches me from my writing. Handwriting connects me.

And, on a more practical front, there’s no doubt in my mind that if I want to remember something, I need to write it down – by hand, not by text or by keyboard. Handwriting reinforces new information in a way typing just doesn’t.

If you’ve ever sat down with me for an interview, you’ll know I still take notes by hand. I remember conversations much better that way than if I take notes on my computer while I chat by phone – or, worse yet, if I record the interview and transcribe the notes later. Besides which, I find that once I’ve written notes by hand, I’m farther along in my head in the story I want to tell – there’s something in the act of handwriting that helps me to start the analysis and structure of a piece before I’ve even begun writing. While typing notes engages my “transcriptionist” brain, handwriting them engages my inner storyteller.

All of which means I just can’t imagine my life without cursive.

I will grant that perhaps, just perhaps, there is no place for cursive in the school curriculum anymore. As students master keyboarding at younger ages and take up coding – essential skills for life in the 21st-century – it becomes less crucial to learn that lowercase a, c, e and m never rise above the midpoint while b and d above should reach the equivalent length of p and q below.

I will even concede that cursive may no longer be necessary. But I will not concede that it is no longer valuable.

So I will cling to cursive. I will continue to handwrite my notes and to scribble the beginnings of stories in my journal, even while knowing that sooner or later I will resort to a keyboard for the benefits of speed and efficiency.

And I will teach my child – now only four and just beginning to print – to handwrite, too, even if for her it becomes more an “artistic” skill than a practical one.

I can’t help but imagine, fancifully, that this discussion has happened before. That somewhere around an ancient Egyptian temple, a small group of die-hard hieroglyph experts once sat and lamented the loss of their art form, wondering how civilization as they knew it could survive when hieroglyphics disappeared forever. (“Kids these days,” moans Amenhotep. “They can’t even hold a chisel properly. What is this world coming to?” “I so hear ya, dude,” says Mentuhotepi. “My kids say hieroglyphs are for middle-aged fuddy-duddies.”)

And I can’t help but imagine that, some thousands of years from now, scholars will look at these days in the early part of the 21st century as the beginning of the end of this lovely, charmingly antiquated form of communication we know as cursive.

But in the meantime, I cling to the mysterious and beautiful art form that is handwriting.

And I’ll give you my pen when you pry it from my cold, dead hands.