The mostly forgotten sinking of the S.S. Pacific has punched its way back into North Vancouver remembrance. Recent salvagers claim to have found the wreck, and hopes are high of recovering perhaps several million dollars worth of gold.

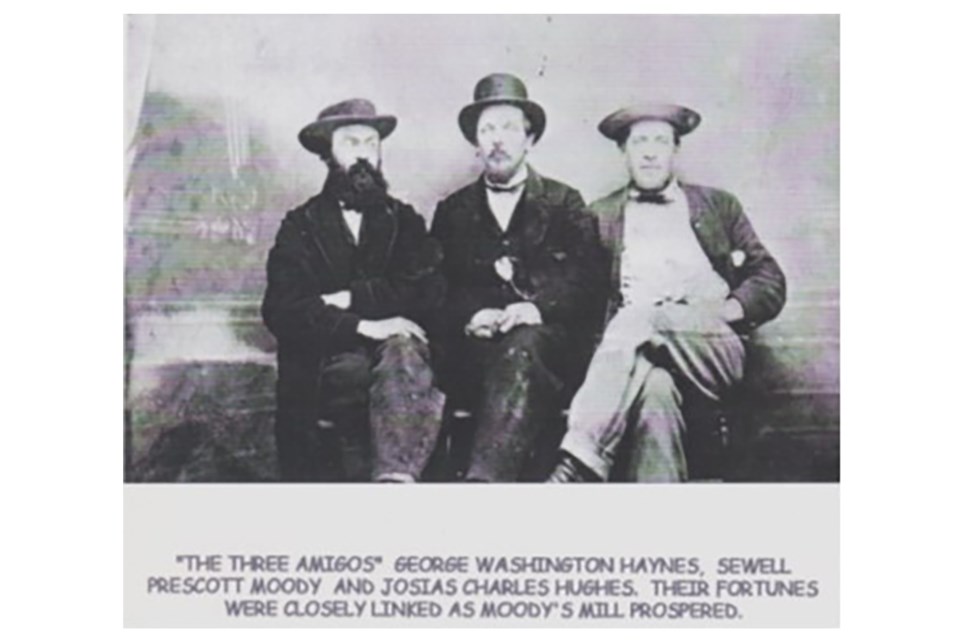

On a cold November day 147 years ago, the ship Pacific sank off the Washington coast. When leaving Victoria six hours earlier, the death ship was officially carrying 250 passengers, but possibly as many as 500 were onboard. While the death of each individual was tragic, of particular note was that the owner of the Moodyville Mill, Sewell Prescott Moody, was among those who died.

An early entrepreneur of the Burrard Inlet harbour area, Moody had purchased a failed lumber mill operation on the North Shore in about 1865 and had guided it to considerable success.

Pursuing business interests in San Francisco, Moody had booked passage on the ship Pacific. Previously the ship had literally been abandoned due to its rotting condition, but when the B.C. Cassiar gold rush took off, transportation for the hoards of U.S. would-be miners became extremely profitable. The ship was refloated and supposedly reconditioned, although workers later reported that they had shovelled out rotten wood from the hull. Apparently, any work that was done was largely cosmetic.

The Pacific was in the charge of Captain Jefferson Davis Howell. Howell’s sister had married Jefferson Davis, who was Civil War president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. The Captain was named in the president’s honor.

While much maligned for this disaster, at 16 years of age Howell had served with distinction during the Civil War and had left service as a lieutenant. At a later time he was also hailed as a hero, credited with saving many lives during the grounding of the passenger ship Los Angeles.

The Pacific was a “paddle wheeler,” similar to the type common to the Mississippi River. After leaving Victoria, the ship steamed through the Juan de Fuca Strait and headed out into the Pacific Ocean and south along the Washington coast. It was later verified that the ship’s lifeboats on one side had been filled with water to counteract the ship’s list.

At the same time, the sailing ship Orpheus was heading north to load coal from Vancouver Island. The ship’s captain, Charles A. Sawyer, observed the Pacific bearing down upon him, but due to bad luck or bad sailing, was not able to avoid the collision.

While the impact was certainly cause for concern, the damage to the Orpheus was relatively minor. After ensuring his ship was not at peril, the captain looked for the Pacific but later reported there was no sign of it. There was “grumbling” by the crew because the other ship (Pacific) had not stopped to offer assistance. Unfortunately, there was good reason for this oversight. The Pacific was at the bottom of the ocean.

It appears the paddle wheeler broke up and sank within minutes of the collision. While there were as many as 20 initial survivors, only two would eventually be rescued. The frigid water and wind were unendurable for most. How quartermaster Neil Henly and CPR surveyor Henry Jelly were able to withstand such conditions for three days is remarkable.

As to possible salvage riches, it is quite probable that many of the gold miners on board were carrying the results of their labours back to San Francisco. Before the voyage Captain Howell was reported to have sold his interest in a Fraser River vessel for $40,000 in gold, and Francis Garesche was on board to escort a $79,000 Wells Fargo shipment placed aboard the Pacific in Victoria. What the values would be today is difficult to imagine.

While the potential salvage of the gold will drive the recovery, it is the potential recovery of artifacts which would most be of important historical value. When the Pacific sank in 1875 it took with it the man most responsible for North Vancouver’s early economic development. Sewell Prescott Moody’s last communication, which washed up on shore, was a recovered piece of wreckage that bore the inscription S.P. MOODY. ALL LOST. It would be fitting if those last words could in some way be amended to ALL REMEMBERED.

Forty-three years later, in a twist of fate, Sewell’s nephew Sewell Moody Dalby was to die in the sinking of the Princess Sophia. Similar to the Pacific, the exact number of deaths is unknown, but it is certain these were the two of the worst sea disasters ever off North America's West Coast. Unlike the Pacific sinking, the Sophia struck a reef. At least 360 died. There were no survivors.

Rick Buchols is a former District of North Vancouver councillor. This article is extracted from his soon to be completed book, North Vancouver Stories.