Nothing says “lab” like a set of calipers and a treadmill test that involves hooking your subject up to a breathing hose.

This is the realm of Fortius Sport & Health exercise physiologist Elizabeth Gnatiuk, and I have fallen into her clutches.

Part one of our appointment involves some pinchy-looking calipers.

Finding out Gnatiuk is a qualified “anthropometrist” does little to put me at ease, but it turns out that’s not as sinister as it sounds.

Besides being an exercise physiologist, Gnatiuk is also a “people measurer,” and the calipers she uses are quite harmless.

Gently pulling the skin from eight different parts of my body (bicep, tricep, shoulder, hip, thigh, calf, and two different places on my tummy) with her thumb and forefinger, she uses the calipers to measure the “soft tissue” (a.k.a. subcutaneous fat) in each spot.

Using a tape measure, she then measures five different “girths” – arm, waist, hip, thigh and calf.

Each measurement is taken at least twice and carefully conforms to protocols set out by the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK).

By itself, this basic body composition assessment is useful as a general health indicator that puts me right in the middle of the healthy zone, according to Gnatiuk.

But one test in isolation is not very exciting.

“When it gets exciting is when you come back,” Gnatiuk says. “You have a goal, you go away, you train, you have a diet program that you’re working with, and then you come back and you see the changes.”

And because she’s an ISAK certified pro with a two per cent margin of error or less, Gnatiuk’s clients can be sure the changes are real and not the result of measurement error.

The second part of my time with Gnatiuk involves more effort from me than being gently pinched all over.

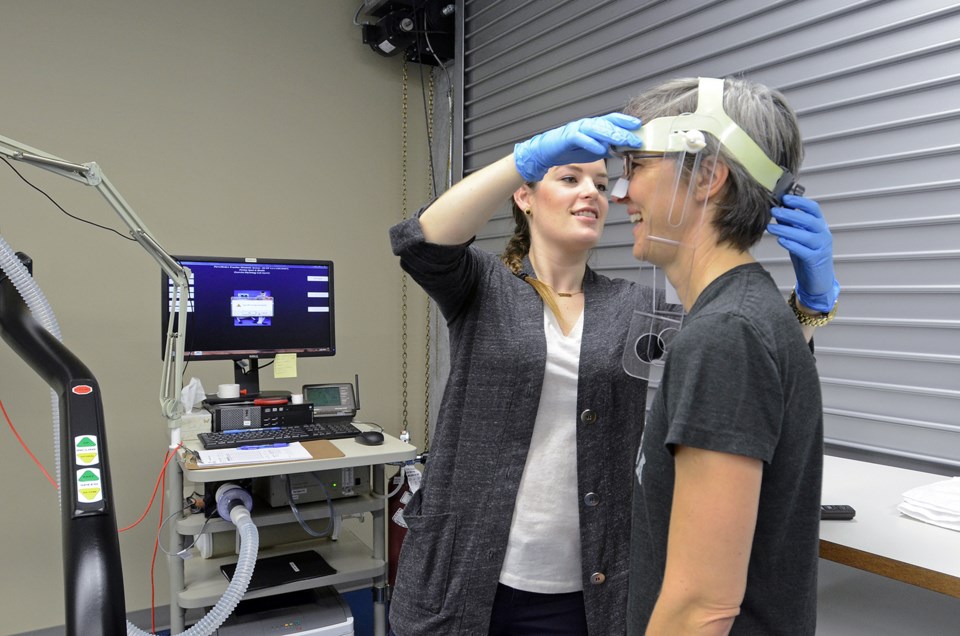

After plugging my nose with a clip and hooking me up to a snorkel-like mouthpiece attached to a hose outfitted with a one-way valve, she sets me on a treadmill.

“I’m just going to increase the intensity until you can’t go anymore,” she says.

The point of this so-called ramp test is to gauge my aerobic power, or VO2 max, which basically shows how efficiently my body produces power out of the air I breathe.

The snorkel-hose is designed to collect everything I exhale and funnel it into an automated metabolic gas-analysis system.

Gnatiuk also measures my maximum pulse and breathing rate.

It’s supposed to be a minimum six-minute test, but as the whirr of the treadmill grows into a higher and higher pitched whine, I call it quits at 5:27.

Panting, I ask whether there is any conclusion Gnatiuk can still salvage from the prematurely aborted test.

“You like to stay in your comfort zone is what it told me,” she says wryly.

Like a lot of recreational runners, I do most of my running in the “junk zone,” which Gnatiuk describes the “comfortably uncomfortable” intensity folks like me gravitate to because we want to work out hard enough to get sweaty and feel like we’ve done something, but not hard enough to reach maximum thresholds.

It burns calories, to be sure, but it won’t lead to improvements in performance, Gnatiuk says.

To do that, she encourages athletes to polarize their training into workouts that are mostly either very easy or very hard.

Counter-intuitive as that sounds to the recreational athlete, elite runners, cross-country skiers, rowers, cyclists, etc. have been training that way for years.

Gnatiuk can help by testing weekend warriors and elites alike, giving them targets to work with and baseline data to measure improvements against.

After my tests, she presents me with a sheaf of papers showing my results.

If I’m serious about making improvements, she suggests I use them to push myself out of my comfort zone, possibly with the help of a Fortius conditioning coach who would work in collaboration with the lab.

“That’s what I do,” she said. “I eliminate guessing. This is what it is whether you like it or not. This is what you need to do. It makes you accountable, and you know you’re working exactly where you need to. That’s my motto – guess less.”

Next stop, hydrotherapy.