Helmut Lemke was only 17 years old when he was conscripted to the Russian Front.

The German teen received draft papers to join Adolf Hitler’s extreme military organization, the SS. At first, people could join of their own free will, but it eventually became mandatory.

“I didn’t go to the draft,” Lemke tells the NOW during an interview at his Burnaby home – one he’s lived in for nearly 60 years. “People told me, ‘Listen, that’s dangerous.’ If you refuse, you can be shot.’ I thought I had the law (on my side), because if it’s voluntary, they can’t draft you into it. ”

About two weeks later, after nothing happened, Lemke got scared. He put in a volunteer application to the German air force and was accepted. Given that there weren’t enough airplanes for the number of pilots around (Lemke had a glider’s licence), he and some others were transferred to the army.

“As a young person, war was some kind of adventure. And so, I was curious what it would be like. I thought I’d make the best of it.”

Luckily for him, he was never seriously injured – at least compared to his comrades. While on the Russian Front in early 1945, a piece of shrapnel grazed his head, causing him to pass out.

“I fell into the snow. When I came to, I saw the snow was red. Then my shoulder blade was shattered,” says Lemke, adding it took him six months to recover.

On another occasion, he recalls a very close encounter with the enemy during the daytime. Sixteen tanks were making their way toward the German front line, and Lemke only had a rifle on him. As he retreated back into the nearby forest to grab an anti-tank missile, he heard voices.

“There were three Russian soldiers coming at me, maybe 20 or 30 metres away. They had automatic weapons and had ammunition necklaces around them,” he explains. “I could not run away. They would have noticed me.”

Lemke proceeded to stand completely still, hoping the soldiers would mistake him for a tree.

And so they did.

“Only my eyes were moving. ... That was a moment where I thought, ‘Anytime, I could (die).’”

Lemke admits if he could defend himself, he wasn’t afraid.

“If you were in danger, you always thought, ‘How can I get out of this? So it got your mind trying to find solutions.’ If I have that, I wasn’t desperate; I wasn’t panicked.”

He was never a member of the Nazi Party, he adds, and neither were his parents.

“I sympathized a little bit at the beginning,” he says, noting his country was very poor after losing the First World War and having to make war reparations for decades. People didn’t have enough food to eat, and the unemployment rate had skyrocketed.

“If somebody says, ‘I’ll get you out of it, they (the people) said, ‘Well, let him try; let’s see what he can do. And if he gets out, we can get rid of him later on,’ but that didn’t work out,” says Lemke.

Following the war, Lemke embarked on a journey to track down his mom. The pair were reunited and escaped from East Germany to West Germany shortly after.

He went on to get a degree in architecture in Germany, then immigrated to Canada in 1955.

He eventually got married and had three children with his late wife, Hildegard.

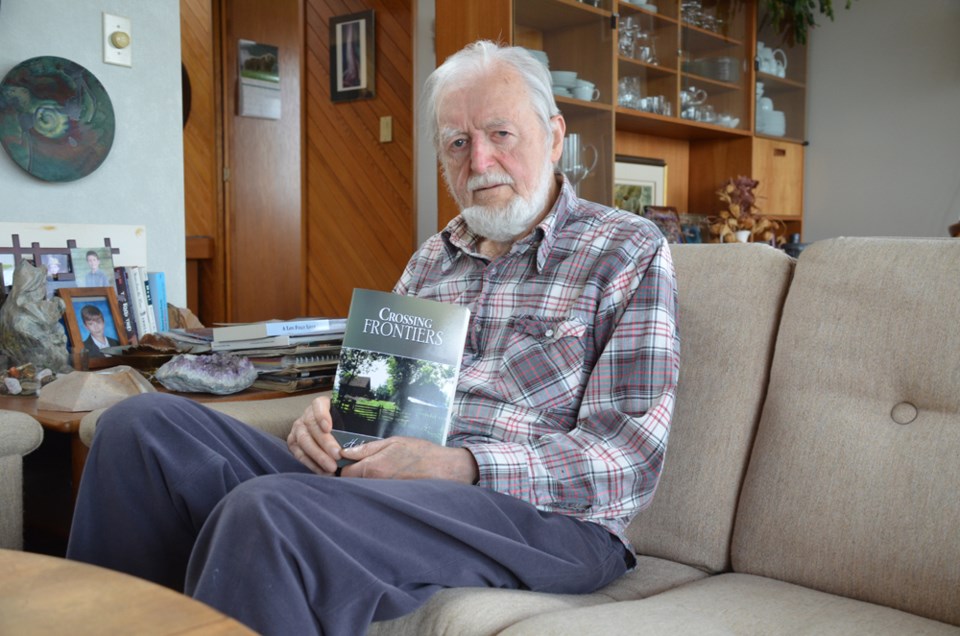

All of his experiences during the war can be found in his book Crossing Frontiers, a book he wrote for his kids.

For Lemke, Remembrance Day is about remembering those people who were forced into war, and whose lives ended too soon.

“Every solider is trained to kill. And that’s the same if they’re Canadian, American, Russian or German, and that is not easy to do. If you are opposite somebody you don’t know, who might be a farmer, a teacher, a lawyer, a father, a son, or husband, to shoot him and make a woman a widow or children orphans, it is not easy to do that.”