A Burnaby lawyer who is offering his services free of charge to people who want to reclaim Indigenous names lost during colonization and at so-called Indian residential schools, says a lot of barriers remain despite a federal process announced last month to help.

Enabling residential school survivors to reclaim their Indigenous names is one of the Calls to Action that came out of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report in 2015.

Staff at residential schools routinely stripped students of their Indigenous names and replaced them with Euro-Canadian ones, according to the report.

The report also includes numerous first-hand accounts of survivors who remember being referred to only by special numbers they had been assigned upon entry into the system.

Call to Action 17 calls on all levels of government to waive administrative costs for name changes on official identity documents, such as birth certificates, passports and driver’s licences, to help residential school survivors to reclaim their lost names.

‘No one told us about this’

The Trudeau government committed in 2015 to “fully implement” the Calls to Action, but no policies were put in place for Indigenous name reclamation until last month after the discovery of 215 suspected unmarked children’s graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in May.

And that policy appears to have been rushed out the door, according to Burnaby immigration lawyer William Tao.

“A lot of details weren’t ironed out,” Tao told the NOW.

He questions whether the government consulted adequately with Indigenous communities before unveiling the policy.

“Our feedback from community members has been like ‘No one told us about this,’” Tao said.

'Potential trigger and trauma point'

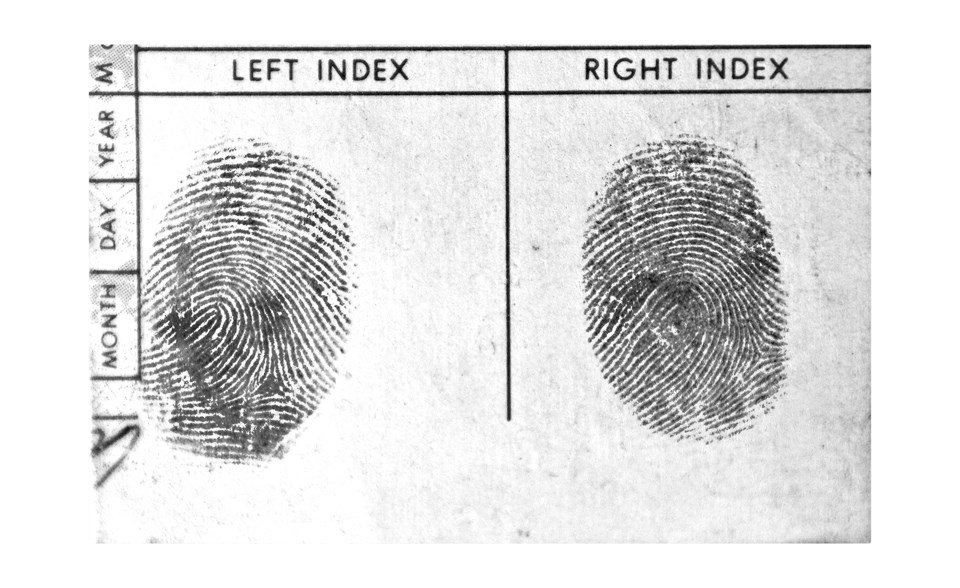

Take fingerprinting, for example.

The City of Burnaby is currently working on a change to its police services fees bylaw that will make it explicit that the local RCMP detachment’s $60 fingerprinting fee won’t apply to “Indigenous peoples, residential school survivors and their family members changing to Indigenous names,” according a recent report to the city’s financial management committee.

The change would bring the bylaw in line with similar federal fee waivers, the report said.

Getting fingerprints taken is one of the first steps in a provincial name-change application, and provincial ID is required to apply for name changes on federal documents, like passports and citizenship certificates, according to Tao.

But paying fees may be the least of an applicant’s concerns when it comes to the fingerprinting process, he said.

“The fact that these provincial processes almost always require fingerprinting or require an Indigenous applicant to go to a police office to get their fingerprints is a potential trigger and trauma point,” he said.

Danita Bilozaze, a Vancouver Island woman who became the first person in Canada to reclaim her Indigenous name under Call to Action 17, agreed.

The first step in her journey began at an RCMP detachment getting fingerprints.

“I am a school teacher, so I am a law-abiding citizen and stay between the lines, and I felt intimidated going in there,” she said.

For other members of her community, she said the experience might be “terrible.”

Police officers were often responsible for taking Indigenous children from their families and taking them to residential schools, and Indigenous people have long been overrepresented in Canada’s criminal justice system, according to Don Johnston, director of Simon Fraser University’s Office for Aboriginal Peoples.

“In my family, my mother and aunt and uncle, when they went to residential school, they were actually picked up by the RCMP and taken to residential school on the way home from work,” he said.

With that kind of history, he said some Indigenous people may not be comfortable going into an RCMP detachment to reclaim their names.

He said Indigenous people may also be leery of what use will be made of the prints once they are taken.

Johnston also said names and identity in the Indigenous community are “probably a lot more complex than the government realizes.”

For Johnston it comes down to consultation.

“They want to address a wrong, so, to be able to do that adequately, they should be talking to the people that were wronged.”

Gaps in the process

The federal announcement of the policy last month pointed to a “formal process” now in place for all Indigenous people to reclaim traditional, ancestral names.

But Tao, an immigration lawyer, said there are a lot of gaps in that process that need to be addressed.

“Applicants who are looking at that website are really confused,” he said.

For one thing, the federal webpages contain no links to provincial agencies and forms required to start the process, he said.

The current federal system also can’t accommodate some characters used in Indigenous names but not used in English or French.

But the biggest barrier in the current process, according to Tao, is just a general lack of education about it.

“Your job is not done by putting up instructions,” Tao said.

'It's our identity'

Bilozaze said getting help from someone like Tao would have saved her a lot of grief on her journey to reclaim her name.

She said she spent eight months in daily battle with numerous federal and provincial agencies before she managed to get the last of her documents changed into her Indigenous name shortly before the “formal process” was announced in June.

Her reclaimed name, Bilozaze, means “the makers” in Denesųłiné, the language of Łuechok Túe, the Cold Lake First Nation.

It points to her family’s traditional role as a people who work with their hands, she said.

When she first explained the meaning of the reclaimed family name to an aunt, she said her aunt had cried and told her it felt as if a missing piece had fallen back into place.

“It’s our identity,” Bilozaze said.

But not enough has changed since the federal announcement on the name reclamation process, according to Bilozaze, and she’s concerned others in the Indigenous community who aren’t school teachers with masters degrees like her, won’t get as far as she did.

“I’ll always keep going back to my mom,” Bilozaze said. “She’s elderly, and she does not have a lot of fight left in her, so I could just see her caving in and paying the fees or maybe just giving up.”

For more information about free help negotiating the Indigenous name reclamation process, contact Heron Law [email protected].

Follow Cornelia Naylor on Twitter @CorNaylor

Email [email protected]