Compared to the average hockey player, a goaltender presents a vast canvas for artistic expression. From custom-designed pads to uniquely-painted masks, a goaltender’s gear is an opportunity to be creative and show some personality.

When Braden Holtby signed with the Vancouver Canucks, he knew he needed new gear for the occasion and, most importantly, a new mask. That meant turning to his long-time mask designer David Gunnarsson, who designs many masks for NHL players, including former Canucks Jacob Markstrom and Eddie Lack.

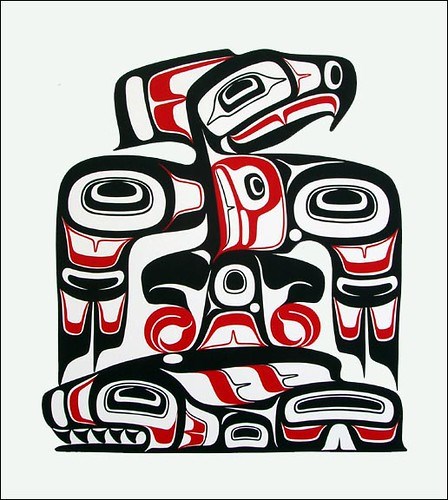

The new mask design from Holtby and Gunnarsson sparked controversy, however, when Gunnarsson posted the mask on his Instagram. It was clearly inspired, if not directly copied from, Indigenous art of the northwest, but the Swedish Gunnarsson is not Indigenous.

Here’s a look Braden Holtby’s new #Canucks mask courtesy of artist David Gunnarson on IG: pic.twitter.com/z1K5eA1rUE

— Rob Williams (@RobTheHockeyGuy) December 11, 2020

“I wanted to make sure I apologize to anyone I offended,” said Holtby in an interview with CTV News. “It was definitely not my intent and I definitely learned a valuable lesson through this all and will make sure I’m better moving forward.”

Holtby made it clear that he wanted to connect with his new home in Vancouver by incorporating Indigenous art into his mask.

“The goal was and still is to include Indigenous artist and try and pick their brain to see how they would design a mask to best represent the history and culture around this area especially because it’s so vast,” he said.

According to Gunnarsson, it was Holtby’s idea to use the Thunderbird, one of the most powerful spirits in Northwest Indigenous myth. The Thunderbird is a common sight atop totem poles, such as the famous Thunderbird House Post totem pole in Stanley Park, a replica by carver Tony Hunt of the original by Kwakwaka’wakw artist Charlie James. In fact, that appears to be the exact Thunderbird used by Gunnarsson in his design.

Same thing, but paired with spooky music pic.twitter.com/cZLcEZLLkK

— Rob Williams (@RobTheHockeyGuy) December 11, 2020

In the case of the Thunderbird design, James's family has been clear in the past that they don't appreciate reproductions of his work without credit.

"My grandfather’s totem pole in Stanley Park is one of the most appropriated Indigenous designs anywhere," said Kwakwaka’wakw artist Lou-ann Neel to The Discourse in 2019. "With no acknowledgement that that’s his work... It pains me to see some of the really poor reproductions of it. It’s just troubling to see that."

In his Instagram post, which has since been deleted, Gunnarsson related the tale of how the Thunderbird was big enough to snatch up killer whales from the ocean in its claws. One of those killer whales, or orcas, is depicted on the bottom of the mask below the cage.

The killer whale appears to be a replica of a piece of artwork by Doug Zilkie, a non-Indigenous artist that has been working in the Haida style for most of his life. The piece is titled “Thunderbird and Whale.” The main difference, aside from the colours, is a change in the teeth to more closely match the style of the Canucks’ orca logo.

Thunderbird and Killer Whale. Doug Zilkie - Lattimer Gallery

Thunderbird and Killer Whale. Doug Zilkie - Lattimer Gallery The mask immediately raised concerns of cultural appropriation from many on social media. Others dismissed the concerns, including some Indigenous people who were happy to see Indigenous art taking such a prominent place in the world of hockey.

“I hope that this can be a good learning experience.”

According to Eliot White-Hill, Kwulasultun, a Coast Salish artist and storyteller from the Snuneymuxw First Nation, the issue is not that Holtby wants to use Indigenous art on his mask, but that it was not done by an Indigenous artist.

“The appropriation of Indigenous art is harmful,” said White-Hill. “For me as a Coast Salish person it is significant that Coast Salish art and Coast Salish artists are represented within our territories. I think of the potential for respect and representation to be shown and how much it would mean to see that done in a meaningful way, and what that would mean for future generations seeing themselves represented.

“So it makes it very frustrating when there are opportunities and interest for respecting and holding up Indigenous cultures and art and instead of doing that and going to the source, the choice is made not to and instead to use methods that are appropriative.”

There’s certainly a place for Indigenous art on the ice, said White-Hill, specifically mentioning the work of Debra Sparrow, a Musqueam artist, on the Team Canada jerseys for the 2010 Olympics. That logo also incorporated a Thunderbird.

“I appreciate that Braden Holtby felt it important to connect with the regional Indigenous culture here in B.C. and that he wanted to celebrate and honour it with his mask,” said White-Hill. “That is important and I am glad for that. I hope that this can be a good learning experience, and I hope we continue to see opportunities to celebrate Indigenous culture in the NHL.”

“We just want to make it authentic.”

The Canucks play on the unceded territory of the Coast Salish peoples — the Squamish, Sto:lo, Tsleil-Waututh, and Musqueam Nations — so incorporating Coast Salish art would be appropriate. That’s not what appeared on Holtby’s mask, however.

“The design is not Coast Salish. It’s a Kwakiutl or Kwagiulth totem pole design,” said Xwalacktun, an artist and carver with Squamish and Kwakwaka'wakw ancestry. “It should be designed by a First Nation. It’s pretty simple: if there’s First Nation art, it should be done by a First Nation artist.”

At the same time, Xwalacktun wanted to be clear that he laid no blame at anyone’s feet.

“We're trying to be kind, we don't want to throw a negative towards the other artist that wants to put the artwork on the helmet,” he said. “But at the same time, we just want to make it authentic.”

One of the issues with working with a non-Indigenous artist is that it takes work away from Indigenous artists, many of whom are continuing a long family history of creating their specific style. That doesn’t mean that non-Indigenous artists can’t work with a particular Indigenous style — Doug Zilkie is an example of an artist doing exactly that — but it must be done in the right way.

“I think it could be a collaboration,” said Xwalacktun. “It’s making that connection with First Nations artists. If he wanted to use his artist, he could just collaborate with a First Nations artist to help design it, then he can put it on the helmet. Then it wouldn’t be an issue, as long as the other artist has been acknowledged.”

“People thought it was going to be lost forever.”

In some cases, non-Indigenous artists have helped keep Indigenous art alive and in the public discourse.

“If you look back into the early 50s-60s, northwest coast art was supposedly dying out and anybody that showed any kind of interest you know was welcomed into the communities,” said Calvin Hunt, who is cousin to Tony Hunt who carved the Thunderbird House totem pole in Stanley Park and apprenticed under him early in his career.

Hunt brought up famous art historian Bill Holm as an example.

“Bill’s knowledge of the northwest coast art and even the language really impressed the people and they ended up adopting him, because there was somebody that was trying to hold on to the art,” said Hunt. “People thought it was going to be lost forever.”

With that in mind, Hunt seemed understanding of the use of Indigenous art on Holtby’s mask.

“Some people will agree with it and some people aren’t. It’s been going on forever,” said Hunt about non-Indigenous artists working in Indigenous styles. “You know what, that design is done really well. A lot of guys don't have the ability to do what that guy came up with. It’s nicely done. It looks like it’s taken right off of that iconic totem pole that’s been used in posters and for advertising for Stanley Park.”

Still, Hunt leans toward giving more opportunities to Indigenous artists.

“There’s some great artists around and there’s always that dilemma as to why people go outside of the Northwest Coast community,” he said. “My thing is, there's so many artists out there. Why does Holtby go to this other artist?”

One of the benefits of working with an Indigenous artist is more familiarity with the style and its history. The combination of the Kwagiulth-style Thunderbird and Haida-style killer whale would be less likely, unless Holtby was specifically looking for a combination of multiple styles.

“I don't know if Holtby wanted to use Kwagiulth art,” said Hunt. “I don't know if that artist knows what he did. Does he know the difference between the different tribes and the cultures, I don't know.”

Canucks and Indigenous art

Holtby isn’t the first Canucks goaltender to take inspiration from Indigenous art for his goalie mask. When Ryan Miller joined the Canucks, he worked with his mask designer Ray Bishop for a blue and green totem pole design. Like Holtby’s new mask, it featured the Thunderbird, this time on the chin.

This mask was not done in collaboration with an Indigenous artist. In fact, with his masks, Miller often does the initial sketches himself.

Then there is the Canucks orca logo, which features elements of Haida art in its design. The logo was designed by Brent Lynch, seemingly without input from any Haida artists. In the years since, the Canucks have formed a stronger relationship with the people of Haida Gwaii, resulting in the Council of the Haida Nation giving the Canucks a Haida legacy art piece in 2013.

One element of Indigenous art connected to the Canucks that is fully authentic comes from Fin, the Canucks mascot. He had Xwalacktun design several of the drums that he uses in Rogers Arena.

Xwalacktun’s rendition of the orca logo, on @CanucksFIN’s new drum, is glorious. pic.twitter.com/7nlgCHMjXw

— Johnny Canuck (@iamjohnnycanuck) October 3, 2018

Even as he works on Fin’s drums, Xwalacktun is always careful to lay no claim to the design of the Canucks’ orca.

“I still put their trademark on it, but I just add a little flavour,” he said. “I don’t put my bear paw beside it, I put it on the side of the drum, because I’m not taking ownership of the Canucks logo.”

“I hope they win the Stanley Cup before I die.”

Holtby made it clear that he won’t be wearing the mask designed by Gunnarsson, but there could still be some new Indigenous art hitting the ice when the next Canucks season start. With Holtby intending to work with an Indigenous artist, his next mask should be more authentic.

Whatever mask Holtby ends up wearing, Calvin Hunt just hopes he’ll be on top of his game.

“I’m a Canucks fan too, so I’m just waiting,” said Hunt. “I hope they win the Stanley Cup before I die.”