People who live in condos and apartments have an extremely low rate of survival after sudden cardiac arrest.

That’s because it takes more time for first responders to reach a suite than enter through a single exterior door, according to a study released March 5 by St. John Ambulance and IPSOS.

Most of the 45,000 Canadians who die each year due to cardiac arrest do so outside of a hospital, said the ambulance service.

Access to Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) combined with CPR could go a long way to closing the gap in survival rate for people living in condos and apartments. But 80% of British Columbians are unable to either locate or access an AED within the crucial seven to 10-minute survival window.

It’s not for lack of expertise: The poll reports that 78% of British Columbians would be willing to use an AED, if available, to save someone’s life.

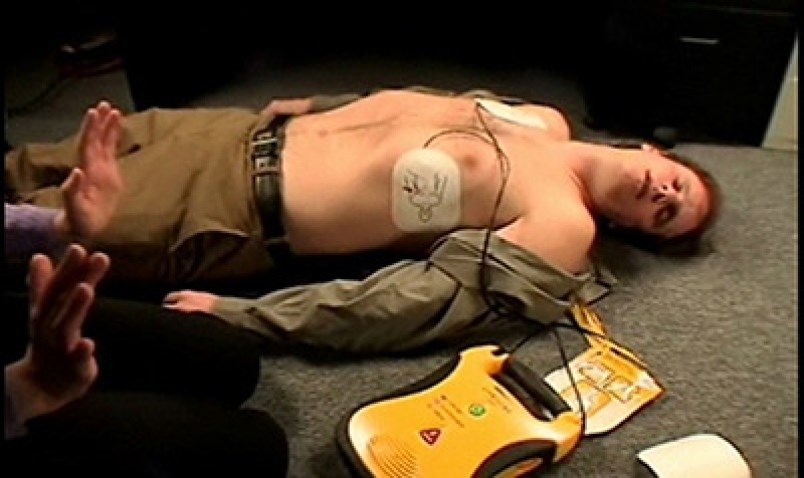

“AEDs are highly automated,” said Karen MacPherson, St. John Ambulance’s CEO. “For most units, you simply push one button, follow the verbal prompts or a picture to apply self-adhesive pads to a person’s chest, and the device guides you through each step to save someone’s life.”

The first minute after a heart attack is crucial. If a patient is defibrillated with an AED in that window, their chance of survival sits at nearly 90%, said St. John Ambulance. But with each minute that passes, the chance of survival drops 7% to 10%. At three minutes, brain damage starts to set in.

St. John Ambulance is calling for every condo or apartment building to install an AED. The cost, it said, averages out to a few dollars per strata unit.

The appeal comes less than a week after B.C.’s auditor general Carol Bellringer levelled a warning to paramedics saying it’s taking too long for them to reach patients with severe injuries and illness, putting people at risk.

The Feb. 27 report went on to say that more needs to be done to bring firefighters in line with B.C. Emergency Health Services.

Ambulance response times in urban areas achieved the nine-minute or less target 50% of the time in 2016 — well below the 70% BCEHS target. In 2018, crews hit that target response time 51%of the time, improving a single percentage point after more staff were added and new procedures put in place.

In some cases, paramedics didn’t arrive for 45 minutes, a number Bellringer admitted was troublesome.

— With files from Diane Strandberg, Tri-City News