Indigenous history in the area dates back nearly 10,000 years, but in the course of the 20th century and to this date, the mountain has been shaped and altered without their input.

To find the full index of stories in this series, see our Jammed Gears landing page.

A tangle of trees lines the shores of the Burrard Inlet, a blend of coniferous trees whose evergreen peaks peer over the water and deciduous trees, naked limbs still awaiting their spring buds.

Today called Barnet Marine Park, the beach and well-groomed park stand in contrast with the wilds that tower overhead. Not long ago, however, these shores were known not for the park but for a very specific type of tree – one known for its peeling bark.

The Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) people called it Lhuḵw’lhuḵw’áyten (pronounced “Thluk-Thluk-Way-Tun”), named for the Arbutus trees – “lhulhuḵw’ay,” which in turn comes from the word “lhuḵw’,” meaning “peel.” That name, Lhuḵw’lhuḵw’áyten, more literally means “where the bark gets peeled in spring,” according to the SFU website.

Khelsilem, a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation councillor who has taught the language and studied documentation of oral history from the nation’s elders, says Burnaby Mountain itself wouldn’t have had its own name.

“One of the things about our place-naming culture historically is that a lot of the place names are based off of sightlines from the water. So there’s a lot of mountains that don’t have names or a lot of areas inland that don’t really have names within our history,” Khelsilem says. “Most of the place names were more sightline-based from the ocean because our main mode of transportation back in the day was canoeing.”

He notes that not every landmark had a name if it wasn’t part of the regular canoeing travel routes.

“But Lhuḵw’lhuḵw’áyten is sort of the name that’s at the base of the mountain. So if they were talking about that mountain, they would have said ‘the mountain of Lhuḵw’lhuḵw’áyten,’” Khelsilem says.

The earliest archeological find from the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh people in their traditional territory is about 9,600 years old, Khelsilem says, and there have been finds of rock tools identified as coming from the Squamish Valley all around their territory. Khelsilem says one SFU researcher and member of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation, Rudy Reimer, has been doing the work of analyzing the finds and connecting the rocks to their place of origin. (Reimer was not available for an interview for this article.)

Burnaby Mountain is near the southeast corner of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation’s traditional territory. It’s also covered by the Səl̓ílwətaʔ (Tsleil-Waututh) First Nation’s traditional territory and that of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) and kwikwəƛ̓ əm (Kwikwetlem) peoples.

According to submissions by the kwikwəƛ̓ əm First Nation to the now-defunct National Energy Board in August 2014, regarding the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, the mountain and the area around it were used for hunting, gathering wood and plant resources, and for overland travel.

“The mountain also provided prime upland areas for hunting and medicinal and food plant collection, particularly in the early spring when salmonberry, Indian plum, red elderberry, and other plant species important to aboriginal subsistence began producing,” reads the submission.

No archeological sites have been found on the mountain, in the area of the pipeline route, and City of Burnaby’s director of parks Dave Ellenwood wasn’t aware of any on the rest of the mountain. But the submission notes archeological finds “should be anticipated, but are likely low density site types and those that may be difficult to detect in both the developed and remaining forested environment.”

Lacking consultation

Burnaby Mountain is seen towering over Barnet Marine Park. Photo: Dustin Godfrey/Burnaby Now

Burnaby Mountain is seen towering over Barnet Marine Park. Photo: Dustin Godfrey/Burnaby NowDespite long histories in the area, Indigenous communities have rarely, if ever, been consulted about what's happening, according to an SFU academic, who in 2017 spoke to the university's student paper The Peak.

“In the 1960s, First Nations were emerging out from under the thumb of the government, despite the fact that the Indian Act and the government had a lot of power,” William Lindsay, then the director of the Office for Aboriginal Peoples at SFU, told The Peak at the time. “They weren’t asked for their input on building the university. The First Peoples had no say, really, on what was happening on the mountain at that particular time.”

Even today, as the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion gears up construction in the region, Indigenous communities say they haven’t been adequately consulted by the government. That led to court rulings that, in 2018, stalled the pipeline to make way for more Indigenous consultations and, in 2020, dismissed further complaints that Indigenous communities weren’t adequately consulted.

But local Indigenous communities have continued to rail against the pipeline project. In fact, that has likely been the greatest point of contention on the mountain in recent years, with activists and Indigenous land defenders arrested and even jailed in recent years for defying court injunctions. And neither side looks likely to back down at any point.

Beyond the pipeline, Khelsilem says his community has “always been advocating for the recognition of our cultural heritage in our territory,” including things like restoring Indigenous names to landmarks, and that could include Burnaby Mountain or Barnet Marine Park.

“(It’s) an opportunity for the public to engage and learn about the local Indigenous history and to appreciate it the way that I think our people have for many thousands of years. And we've got a lot of really exciting projects in that regard around signage and recognition and things like that,” Khelsilem says.

And there are plenty of opportunities for reconciliation or decolonization in the area, including on Burnaby Mountain, he says.

“There’s a lot of opportunity to partner with First Nations and to do projects together, and there’s lots of opportunities for either co-management of areas within the territory or repatriate the land back to the community.”

As the city looks at planning the future of the mountain, Ellenwood says it’s committed to increasing Indigenous participation in its policies.

“I think the city … has taken a very progressive approach to that, and the mayor’s office in particular has developed an Indigenous consultation processes that allow us to do that. And we’re going to take full advantage of them in this analysis,” Ellenwood says. “There will definitely be an Indigenous factor to this, a study that incorporates not only an archeological asset assessment but a planning and consultative element to this.”

Changing landscape

In old, black-and-white CBC B-roll, found in the Heritage Burnaby website’s archives, heavy, steel-framed cars float in a silver sea speckled with the blemishes of old film. With the buoyant reflex of 1950s suspension, the cars straddle each bump like a wave as they navigate the uneven parking lot on Burnaby Mountain.

In 2021, it would be unusual to see more than a handful of dignitaries and media at a sod turning. But on Oct. 7, 1957, dozens of people greet the cars at an event to watch exactly that, marking the beginning of one of the first developments on Burnaby Mountain.

Frank M. Ross, then B.C.’s lieutenant-governor, gives a brief speech at a podium, brought to the mountain and placed under a tent before turning to his ceremonial duty.

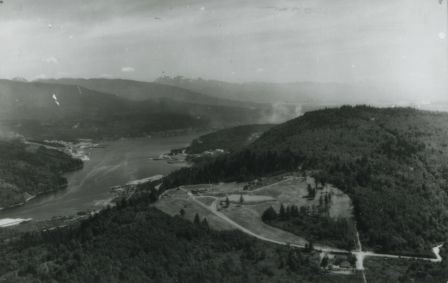

A mid-century aerial shot of Burnaby Mountain, before the university was built but after the construction of the centennial pavilion. By Heritage Burnaby archives

A mid-century aerial shot of Burnaby Mountain, before the university was built but after the construction of the centennial pavilion. By Heritage Burnaby archivesIn his tight black blazer and loose grey dress pants, Ross is no natural with a shovel. But after a few awkward jabs and a little shake, he's able to gain purchase and turn the soil over before his audience.

The sod turning launched the Burnaby Mountain Centennial Project to celebrate B.C.’s 100th anniversary. The project saw a pavilion and park built on the northwest quadrant of the mountain. That pavilion was eventually renovated to house the Owl and Oarsman restaurant before later becoming Horizons, which closed early last year.

Burnaby archival records indicate the park was chosen by the Burnaby centennial committee over eight other proposals to mark the province’s first 100 years.

The view from the surrounding park is about as iconic as it gets in Burnaby. Now, more than 60 years after that sod turning, it’s complemented with a centennial rose garden, created in the 1990s to celebrate the city’s 100th anniversary, and the wood sculptures, gifted to Burnaby by its Japanese sister city of Kushiro, that overlook the Burrard Inlet.

Near the top of the city’s own Mount Olympus, the aptly-named Kamui Mintara – “Playground of the Gods” – sculptures sit where the Burnaby earth meets the heavens, and the natural surroundings are only a reflection of that.

Increasing developments

The finely groomed park is among the first developments on the otherwise natural space, being completed just half a decade after the original Trans Mountain pipeline.

Once called Snake Hill, Burnaby Mountain has always been recognized as a special place in the city. Royal Museum of B.C. archives indicate the province was considering making it a provincial park possibly as far back as 1909, and it was ultimately dedicated as a provincial park in 1942.

In the middle of the 20th century, the vast majority of the mountain was mostly untouched. But since that time, there has been a slow encroachment of development, despite its park designation.

The boundaries of that park were altered in 1952 to accommodate the development of the Trans Mountain pipeline, but according to Heritage Burnaby, “significant conservation and park lands were left untouched.”

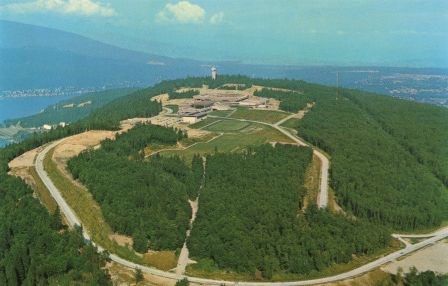

An undated aerial shot of Burnaby Mountain looks out over SFU. By Heritage Burnaby archives

An undated aerial shot of Burnaby Mountain looks out over SFU. By Heritage Burnaby archivesIn one black-and-white aerial photo, taken some time in the 1940s, the Trans Mountain tank farm is the only noticeable mark on the otherwise undisturbed mountain, looking more imposing without the nearby Forest Grove development or Burnaby Mountain Parkway flanking it.

Another aerial photo, taken sometime between 1958 and 1965, shows a blanket of trees over the ridge where Simon Fraser University now sits.

In the decades that followed, more and more portions of the natural space were cleared for development.

At the very top of the mountain, of course, sits Simon Fraser University. Nicknamed the “instant university” when it first opened, SFU turned a design submitted by Erickson/Massey Architects to a 1963 design competition into an operational university just two years later.

The university stands in stark contrast with its natural surroundings, with brutalist architecture – hard angles baked into cement buildings – then seen as “futuristic.”

But despite the architecture, the university still managed to blend into its surroundings, and that’s no happy coincidence. When designing the university, Erickson/Massey, whose original design submission was followed without alterations, specifically designed a “series of horizontal terraced structures … that hugged the ridge and dissolve into the landscape.”

“Tall buildings would have been out of scale with the massive mountaintop ridge,” reads a writeup on the university’s construction in Burnaby’s Heritage: An inventory of buildings and structures, published by the City of Burnaby’s community heritage commission in 2007 (updated to 2011).

As early as 1964, there had been considerations for adding a housing development around the university, but that was never actualized until the mid-1990s – and that appears to have broken with the architectural philosophy of hugging the contours of the mountain. Today, if you look at the mountain from Cariboo Hill, housing complexes and cranes are visible atop the mountain.

With the creation of the Burnaby Mountain conservation area, a line quite literally was drawn between where developments can occur and where they cannot occur. That line was the 500-foot elevation mark, although it has been tinkered with over the years to accommodate neighbourhoods, such as Forest Grove.

But there hasn’t been a clear limit on human uses of the park, and conservationists worry that people are continuing to encroach on the space, affecting the plants and wildlife in the area.

In part 3 of this series, we’ll look at the challenge in conservation posed by human activities on the mountain.

To find the full index of stories in this series, see our Jammed Gears landing page.

Find Dustin Godfrey on Twitter at @dustinrgodfrey