Ninety-five years ago, the majority of Burnaby city council wanted all people of Asian descent to be deported and their land expropriated.

The motion they passed to send that message was forwarded to city council by the Vancouver Ku Klux Klan.

This is one of at least 20 moments in Burnaby’s history that expose the systematic racism in the municipality’s past, according to a recent city report.

The city now promises to apologize for its discriminatory history against people of Chinese descent.

Council approved a plan for reconciliation with Burnaby’s Chinese Canadian community at a meeting on Feb. 27.

The framework plan will be guided by an advisory group made up of members of the local Chinese community, including city staff members of Chinese Canadian heritage and a historical advisor, according to the report.

The group will find actions for reconciliation, including acknowledgements and a formal apology. The city will also come up with an engagement strategy to hear from the local Chinese Canadian community, with outreach in Chinese languages and English.

Systematic discrimination impacts today

Two city councillors expressed the direct impact of systemic discrimination against Chinese Canadians on families living in the community today, including their own.

“My partner’s grandfather came to B.C., landed in B.C. to work on the railroad,” said Coun. Alison Gu.

“He worked as indentured labour; then his wife was not allowed to come over because that was purposeful policy to ensure that Chinese families did not settle here,” said Gu.

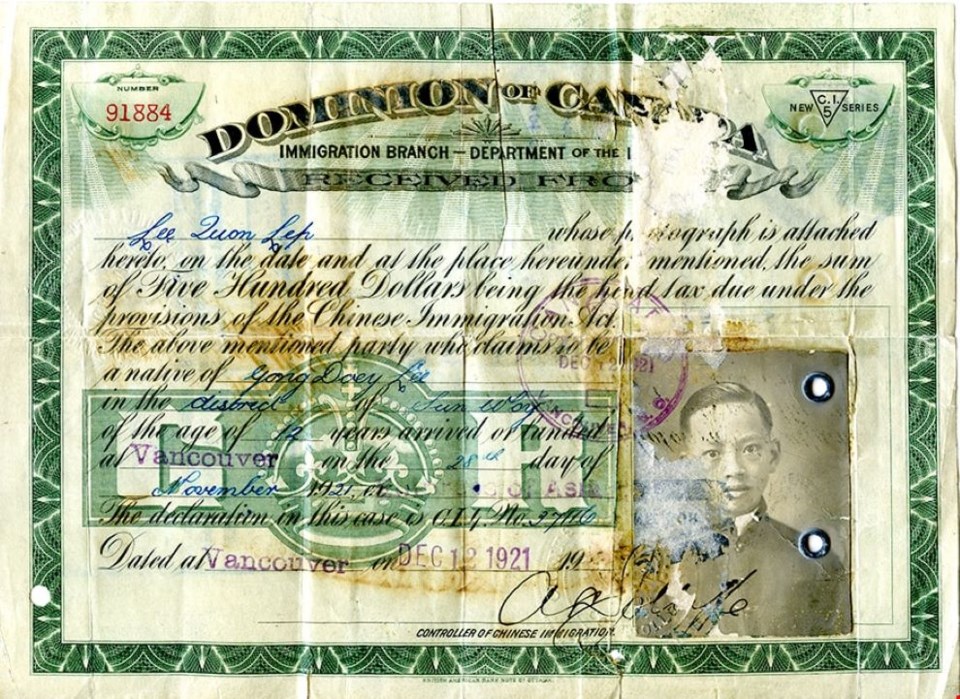

Coun. Richard Lee said his family was affected by policy discrimination, including the Chinese Head Tax, which charged Chinese immigrants $500 to come to Canada and restricted the arrival of Chinese people to Canada.

“My grandpa paid for the head tax in 1913 when he came to this country,” Lee said. “And my family were separated by the Chinese Exclusion Act. So I think this is a long overdue process.”

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 barred Chinese people from immigrating to Canada. It was repealed in 1947.

Gu said city councils, not just federal and provincial governments, directly advocated for and discriminated against Asian immigrants.

“These policies that have restricted access to land, restricted access to good jobs – not even good jobs – jobs, just sustenance, period, and livelihoods, businesses. And the ways that we … weaponized our bylaws to target these groups is something that we need to reconcile with, we need to apologize for, and we need to take very real actions to make reparations.”

More than one-third of Burnaby’s residents today are of Chinese descent, “including new immigrants as well as fourth- or fifth-generation Chinese Canadians who have deep roots in Burnaby,” according to the report.

Historical discrimination

Burnaby’s discriminatory history is summarized in the staff report, which gives a broad strokes outline of the racism faced by Chinese community members and other minorities between Burnaby’s incorporation in 1892 and 1947, when the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed and Chinese Canadians and South Asian Canadians were enfranchised with the right to vote.

Burnaby historically endorsed many racist petitions from residents groups to impose restrictions on Chinese immigration, business licences, and land, according to the report.

In the 1910s to ’20s, Burnaby council rejected a number of trade licences for Chinese Canadian greengrocers, and, in 1922, council endorsed a resolution from a ratepayers association “that no further Oriental retail or wholesale traders be licensed in this municipality.” The B.C. Attorney General’s office at the time denied the request.

Burnaby’s first mayor, Reeve Nicolai Schou, gave testimony in 1902 to the Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration, saying “he would favour almost total exclusion” of people of Chinese origin, according to the report.

“He argued that the presence of Chinese migrants discourage(d) British settlers from clearing the land.”

The city also prevented Chinese and Japanese people from working for the municipality or contracting for the municipality until the mid 20th century.

There were no explicit municipal bylaws preventing the sale of city land to Asian people, but the city report said, “It is clear that Chinese Canadians were largely excluded from land ownership in Burnaby.”

In one case, a petition from local residents in the Heights protested the sale of city land to Asian Canadians, and council “removed from sale all municipal properties in the neighbourhood.”

Mayor Mike Hurley said in a press release the effects of those discriminatory policies continue to be felt in Burnaby today.

“We cannot hide from our past – but we can commit to spending the time and effort to better understand the struggles this community faced, and how we might move forward together.”

Staff estimate the reconciliation work will cost $40,000 in 2024, while work in 2023 is covered by the city’s existing operating budget.

The city has set a target date for the official apology to come in May 2025.

The city will also acknowledge the centenary of the Chinese Exclusion Act on July 1 this year as part of the city’s official Canada Day events.