When Raj Chouhan landed on Canadian soil in 1973, he never imagined he’d become the founding president of the Canadian Farmworkers’ Union and at the forefront of a social movement that would bring farm workers under the Employment Standards Act.

It all started with an ad in a newspaper that advertised the need for workers at a Fraser Valley farm. The then-20-something had seen it and decided to check out the farm. But when he got there, he was shocked by what he found.

“There was no running water, no toilets, absolutely no facilities,” Chouhan, the now-Burnaby-Edmonds MLA, told the NOW. “I was expecting, in a country like Canada, that there would be something better than that.”

Some workers lived onsite in converted cattle barns and were squished in like sardines, with six people to a cubicle, he recalled, adding a good chunk of the little money they did make would go to the contract labourer for rent. Meanwhile, workers were constantly exposed to toxic pesticides and unguarded machinery, and many were forced to bring their children to work because they couldn’t afford daycare, he said.

After asking the farmer’s son why conditions were so bad, Chouhan was fired. The same fate followed him after he asked the same question of two other employers.

“That created an interest, a curiosity to find out what was going on,” said Chouhan. “Nothing was being done to organize or help farm workers. They were not even deemed workers under the Employment Standards Act.”

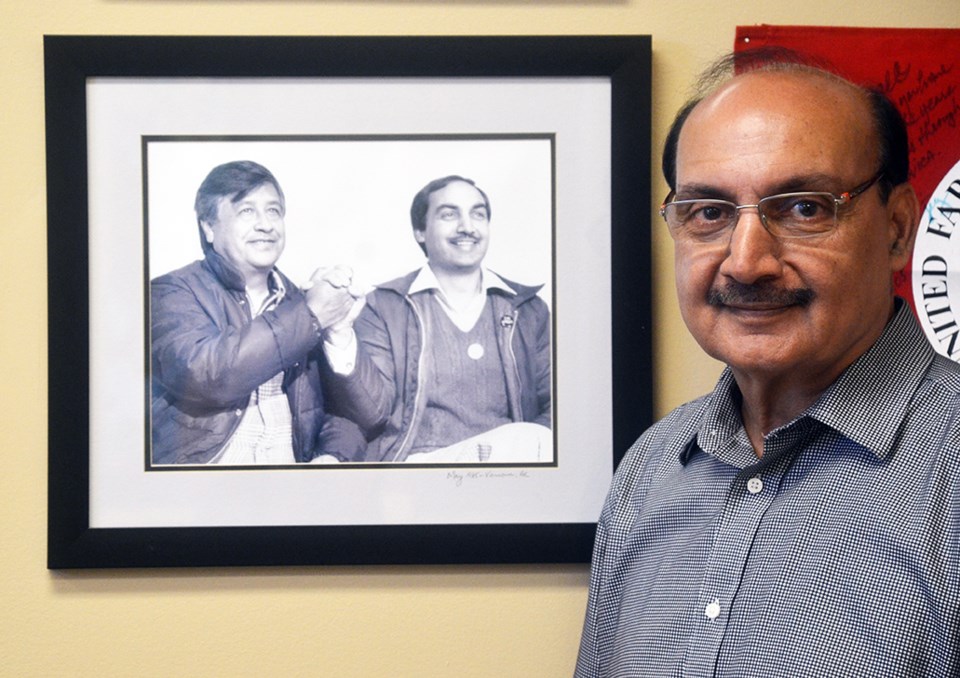

In the years following, Chouhan familiarized himself with labour activist Cesar Chavez, who founded California’s United Farm Workers. (The pair would go on to become friends.)

It took at least five years before the local politician was able to rally a group of farm workers under one roof to talk about their dire situation. Threats, intimidation and bullying tactics were used by the employers to keep the workers quiet.

“They were telling the workers that if you contact any authority, you will be deported. We were meeting them in their kitchens. People didn’t know about their rights, so they were afraid,” explained Chouhan.

In September of 1978, 30 farm workers met Chouhan at a library in Surrey. The following April, the Farmworkers Organizing Committee was struck. About 2,000 members signed up that first year, which led to the establishment of the Canadian Farmworkers’ Union on April 10, 1980.

“It was a moment, for me, personally, like God, is this real? It was like a dream coming true,” said Chouhan.

After gaining union status, the next step was to go out and organize. The task was difficult, however, because most farm workers were seasonal and didn’t have a permanent work address.

The first two employers Chouhan and his team attempted to bring under a collective agreement was a mushroom and alfalfa sprout farm. Both farms were reluctant to give into the demands, so the workers were forced to go on strike for six months.

“The pressure from thefarming community was so much on these two employers because they were afraid that if we were successful here, then we would go to other places. They didn’t want us to succeed,” said Chouhan, adding employers would send in “scab workers,” non-unionized workers, to cross the picket line and work.

Given that the union had limited financial resources, he said union members would pool their money to survive. With a wife and a young daughter at home, times were tough.

“I had no money. My daughter wanted to go to McDonald’s to have a Happy Meal. In order to avoid that, I would make sure I wouldn’t drive on the street that McDonald’s was on because I couldn’t afford to buy it,” he told the NOW.

When the strike ended, it was a huge celebration, Chouhan remembered, but it didn’t last long. Over the next few years, organizing transient farm workers continued to be difficult. Intimidation got to the point that if workers spoke to a union representative, the employer would refuse to issue them a record of employment, which they needed to apply for employment insurance. As a result, union membership began to drop, and by 1984, there were no new collective bargaining agreement certifications. Today, the Canadian Farmworkers’ Union only exists on paper and has no members.

Despite not being an active body, Chouhan said the union helped draft health and safety regulations for the agriculture sector that were adopted by the provincial government in the early ’90s; regulations that still stand today. It also played an important role in educating workers who were illiterate, by teaching them about their tools, pesticides and anything agriculture-related.

Looking back on those years, Chouhan said he’d probably have to think twice about doing it all over again. He admitted there were some “very scary” moments, including a time when he had a gun pointed at him by an employer while he was out handing out pro-union pamphlets.

“At that time, there was a need, and I didn’t think twice at all,” he said.

More than 40 years later, Chouhan still gets stopped in the street and is recognized as the “farm worker organizer.”

“When people go to restaurants, or have dinner at home, they don’t think about where the food is coming from. They don’t think about the people who produce it, who work 12 hours a day under very harsh conditions. We have to think about those people, they’re human beings, too,” he said.