Bobby Baun, a hard-nosed defenceman who entered hockey lore by helping the Toronto Maple Leafs to the 1964 Stanley Cup on a broken leg, has died at the age of 86.

Born Sept. 9, 1936, in Lanigan, Sask., as Robert Neil Baun, he played 17 seasons in the NHL.

The NHL Alumni Association announced his death on Tuesday, but the cause of death was not released.

While weighing in at a "hefty 10 pounds-plus" at birth, he was not a big man fully grown. But Baun would go on to earn the nickname Boomer for his big hits.

The five-foot-nine 175-pounder collected 37 goals, 187 assists and 1,489 penalty minutes in 964 regular-season games from 1956 to 1973. He added three goals, 12 assists and 171 penalty minutes in 96 playoff games.

"Bob possessed unquestionable toughness and incredible pride in being a Toronto Maple Leaf," team president Brendan Shanahan said in a statement. "His inspirational presence continues to embody the heart of the game.

"He will be greatly missed by the team and its fans. Our thoughts are with Bob's loved ones during this difficult time."

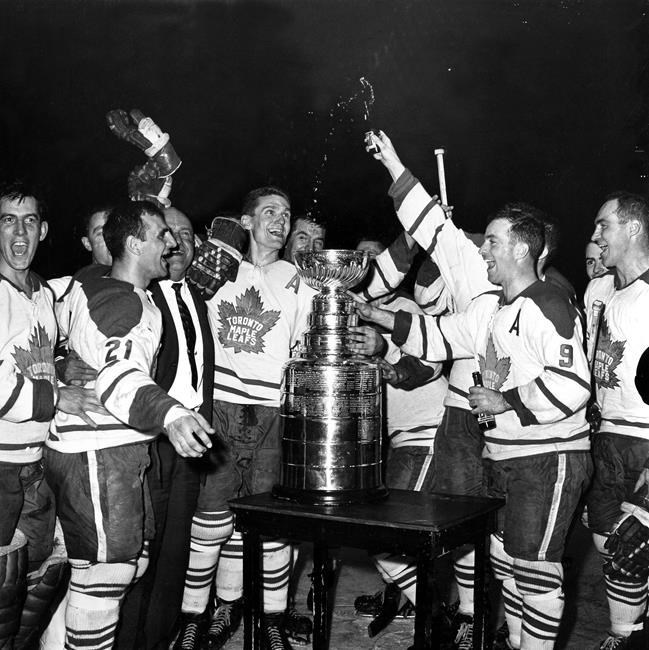

Baun won Stanley Cups with the Leafs in 1962, '63, '64 and '67. But it was in the 1964 final against Detroit that he reached legendary status.

With the Leafs trailing 3-2 in the series, Baun — who had been in the penalty box for two of Detroit's goals — was stretchered off the ice with 13:15 remaining in the third period of Game 6 after blocking a Gordie Howe shot just above the ankle while killing a penalty.

"It was numb then and I couldn't figure out what was wrong," Baun said in an interview after the game. "And then when I went into the faceoff with Gordie Howe, I just heard a snap and it caved in underneath me. And I tried to get up and there was no way I could put any weight on it.

"So that was the story then. They froze my leg then and it's all right right now, of course. I can't feel it with the freezing in there."

After being taken off the ice, he asked the doctors if he could hurt himself any more. They said no.

His ankle frozen and taped, Baun came back late in the third period and scored the winning goal at the 1:43 mark of overtime with a shot from the right point that beat Detroit netminder Terry Sawchuk to give Toronto a 4-3 victory.

"For 'The Goal,' I will always be grateful," he wrote in his 2000 autobiography "Lowering the Boom: The Bobby Baun Story" with Anne Logan.

He called the goal "the high point of 28 years of determination, dedication and desire."

Years later Baun called the shot "A triple-flutter-blast with a followup blooper and it went off (Detroit defenceman) Bill Gadsby's stick and went the opposite way on Sawchuk and in the net."

At the time he thought the injury might be a pinched nerve. Baun could hardly walk, but he played in Game 7 as the Leafs won 4-0 at home to hoist the Cup for the third consecutive year.

Baun had painkilling injections before the game and between each period of the deciding game. So did teammate Red Kelly, who had torn knee ligaments in Game 6.

Weeks later, irritated by the cast he had to wear, Baun soaked his leg in a bathtub until the cast came off.

In an interview years later with hockey host Brian McFarlane, Baun described the time between Game 6 and 7.

"Two nights later, we won the Stanley Cup on home ice by a 4-0 score," he recalled. "I had my leg iced before that game and took shots of Novocain every 10 minutes.

"Only after the Cup was won did I go for X-rays, and they found a broken bone just above the ankle. I was in a cast for the next six weeks. Was it worth it? Sure, it was. That’s how much winning the Stanley Cup meant to me. Most hockey players would tell you they’d do the very same thing."

Baun was a hard man to stop.

"I would say my pain tolerance is high," he said in an interview with the Toronto Star 50 years later. "Pain didn't bother me much. Still doesn't … I played five years with a broken neck and didn't know it."

In 2000, Canadian Press hockey writer Neil Stevens described Baun as a "prototypical sixties hard-rock, body-crunching, stay-at-home defenceman."

That was the year that Baun released his autobiography. While the book came out 36 years after that famous Stanley Cup goal, Baun said he was still getting 3,000 pieces of mail a year.

Baun, then a resident of Pickering, Ont., called the attention "pretty special."

He said his job was to stop goals not score them.

"If I got a goal, that was a bonus," he said.

Baun was ranked No. 30 on the Leafs' top 100 players in 2016 as the franchise prepared for its centennial anniversary.

His family left Saskatchewan for Toronto when he was three.

Baun played junior for the Toronto Marlboros of the Ontario Hockey Association from 1952 to 1956, winning the Memorial Cup in 1955 and 1956 with a stint at the Leafs camp in between. He began his pro career in the AHL with the Rochester Americans, playing 46 games before the Leafs called up him.

His first deal with Toronto paid $8,000 a year plus a $4,000 bonus.

He spent his first 11 NHL seasons with Toronto before being taken by the Oakland Seals in the 1967 expansion draft. He spent one season with Oakland before going to Detroit the next year.

While a Wing, he counselled Howe to ask for more pay, saying he was making "twice as much money" as the Detroit legend. An irate Howe went to Wings’ front office the next morning and team owner Bruce Norris met his demands.

Baun returned to Toronto in 1970 for the final stretch of his playing career.

He retired in 1972 after injuring his neck after a hit by Mickey Redmond. He had previously suffered a neck injury playing for Oakland and doctors told him if he got hurt again, there was a 95 per cent chance he would end up in a wheelchair.

Off the ice, Baun was always good to the fans, citing the example of Bobby Hull.

"He'd sign every last autograph people waited to get," Baun told The Canadian Press in 2000. "I always tried to do the same. People take the time to wait and have an autograph signed, you should have the time to give them the time of day. That's just common courtesy in life, something we don't see often enough any more.

"People don't take the time or don't care about what other people have to say. If you want to talk to me, I'm willing to listen and discuss ideas. That's what's important."

The NHL Alumni Association says Baun's legacy of kindness and compassion will be remembered fondly.

"Not only did he take care of his community, but he was profoundly committed to helping out his (NHL alumni) family every single day to make their tomorrow brighter," the association said in a statement.

After ending his playing career, Baun tried his hand at farming before coaching the Toronto Toros in the World Hockey Association in 1975-76. He did not enjoy the experience much and quit.

He went on to sell houses and cars before joining an insurance company. He later had success in running a Tim Hortons franchise in Pickering and later opened another in nearby Ajax, eventually selling both.

"My other careers were a learning experience, sometimes profitable, sometimes not, but I would not trade any of that," Baun wrote in his autobiography. "But in honest reflection, what has affected my life the most was that goal I scored on April 23, 1964."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Aug. 15, 2023.

Follow @NeilMDavidson on X

Neil Davidson, The Canadian Press