A couple of years ago, Claudia Li's university friend asked her if she ate shark fin soup, a traditional dish often served at Chinese weddings.

Her response was affirmative and a bit defensive.

"I guess it was a knee-jerk reaction, like: You're not Chinese, don't tell me what to do," recalls the longtime Burnaby resident. Li's friend recommended Sharkwater, an award-winning documentary on how sharks are falling victim to human predators. One night, home alone, Li decided to watch the film.

"I couldn't sleep that night," she says. Sharkwater challenged the stereotype of sharks as blood thirsty, killing machines and showed how they are top predators and an important part of our eco-system, Li says. The film claims that shark populations are on a radical decline due to demand for shark fin soup, an expensive dish that signifies wealth in Chinese culture.

"I was not only appalled at how ignorant I was, but I couldn't understand how my community and my people could wipe this large and very important species off the face of the earth for a bowl of soup," Li says.

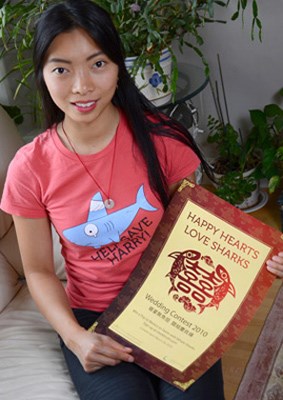

The film left Li feeling sad and disappointed in herself, so she decided to form Shark Truth, a grassroots non-profit group to stop the consumption of shark fin soup in Canada.

Shark Truth runs an annual "Happy Hearts Love Sharks" contest for betrothed couples, challenging them to forgo the usual staple of shark fin soup at Chinese weddings. This year's grand prize is a trip for two to Hawaii to dive with sharks. Li estimates that for every 10 bowls of soup, a shark perishes.

Last year's winning couple, with 680 wedding guests, saved about 68 sharks from slaughter. In the past two years, since the start of the organization, Li figures the group has diverted 8,600 bowls of soup, saving 860 sharks.

Sharks are one of the oldest creatures on earth. They've been around for more than 400 million years and predate the dinosaurs. There are more than 400 species of sharks, but many types can be used for shark fin soup. Numbers vary, due to limited data, but estimates on the number of sharks killed annually can range from 10 million to 73 million, with median figures at 38 million.

The United Nations Environment Programme points to studies showing a 90 per cent collapse in shark populations in the Mediterranean and Gulf of Mexico.

Conservationists criticize the practice of "finning," where sharks fins are sliced off and the creatures are thrown back in the ocean, often alive, unable to swim and left to flounder.

The valuable fins are typically turned into soup and often served at Chinese weddings. It's part of something called the "big four," Li explains. Abalone, shark fin, fish maw and sea cucumber are the four dishes wealthy families often serve. The groom's family often pays for the wedding banquet, Li adds, and serving shark fin soup is a sign of prosperity.

"It's just like this ingrained tradition that a bride marrying into a family without shark fin is marrying into a poor family," she says.

Prices range, depending on how much fin is served, but a bowl of soup can cost up to $300, according to Li.

For families like Li's that have struggled out of poverty, serving shark fin soup is a way to showcasing their success and the virtue of sharing. But Li uses a lesson from her grandmother to challenge the shark fin tradition.

"Chinese people don't like to waste. That was one of the values my grandma taught me," she says. "Shark finning is immensely wasteful."

Fighting the soup and challenging Chinese tradition also meant causing a bit of a disturbance.

"It was very much against the harmony of my family members," Li says. "In Chinese culture, we respect the value of harmony. ... The way I look at it now is the harmony I'm respecting is that harmony for our planet and our ecosystems."

While the younger generation seems to "get it," there's a mixed reaction with the elders, Li says. There's still some fear of losing face by not serving the soup, she adds.

"I am Chinese. I know our people. I know this tradition. Sometimes traditions are hard to kick, but we kicked foot binding. Why can't we kick shark fin soup?"

Li has 10 people working in her group, with the goal to eliminate shark fin soup in Canada in the next five to 10 years. She plans to "franchise" her wedding contest model, so other organizations can copy the idea, and she wants to start a cooking contest with an anti-shark fin twist.

If Li gets married, she plans to do things her way.

"Definitely not shark fins. Probably on the beach, with no shoes and a white slip. Very non-traditional," she says laughing.

For more information on Li's organization, go to www.sharktruth.com.

For more on this story, go to Jennifer Moreau's blog, Community Conversations, at www.burnabynow.com.