You’d think that since Socrates, Plato and Aristotle sat together under the legendary plane tree in Athens around 430 BC, the debate about whether some form of direct instruction or a version of inquiry-based learning is the more effective teaching/learning technique would have been settled by now.

But no — probably because asking whether one system of teaching and learning is more successful than another is the wrong question.

In March 2023, 13 scholars led by Dutch researcher Ton de Jong took on the debate in the academic journal Educational Research Review in an article titled “Let’s talk evidence — the case for combining inquiry-based and direct instruction.”

They made the point that the research on the question is not only convoluted, it doesn’t really establish which system is superior.

Some studies show inquiry is more effective, while others, predictably enough, indicate that direct instruction is better.

How could two groups of scholars look at the same body of research and come to opposite conclusions? Probably because the two groups of scholars had not agreed upon a definition of what it was they were actually arguing about.

So let’s begin with a definition of direct instruction.

According to the Oregon-based National Institute for Direct Instruction, DI is based on systematic, well-planned and explicit instruction delivered by teachers.

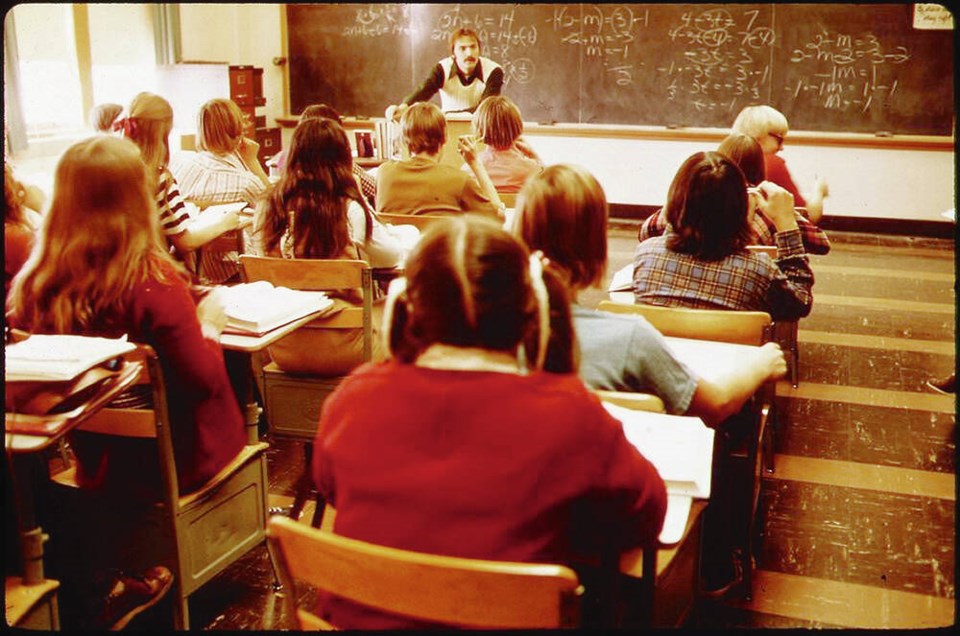

I’ve heard it referred to as the “stand and deliver” system, which has been used in classrooms since the inception of universal public education.

The institute cautions that only 10% of each lesson should be new material and 90% should be revision and practice of existing knowledge.

It is the teacher who drives the entire lesson, but direct instruction at its most effective does not mean that the lesson is all teacher talking and student listening.

Probably the best-known variation is the one proposed by UCLA professor Madeline Hunter.

Hunter’s model for teaching and learning was widely adopted by schools during the last quarter of the 20th century.

The basic lesson plan contains a direct-instruction sequence of the teacher stating the objectives of the lesson, including an anticipatory set (why are we doing this?).

The teacher then models or demonstrates the key elements of the lesson and checks for understanding every step of the way. Students then try a guided practice. There is more checking for understanding and finally students complete an independent practice of whatever the lesson requires.

Inquiry-based teaching and learning, in contrast, begins with the teacher asking students questions and posing problems.

From there, students employ their natural curiosity to research and develop solutions. Students explore the topic through research and hypothesis creation.

Student responses can be in the form of projects, verbal presentations, audio-visual presentations or written papers. Since they are student-driven, inquiry-based activities can play out any number of ways in the classroom. The teacher, a kind of “ guide on the side,” helps students recall and apply prior knowledge to reach a conclusion about the lesson topic.

Next, students share what they have found and teachers help correct misconceptions.

Finally, in the elaborate and evaluation stages, learners apply their new knowledge to different subjects or interest areas, and reflect on their work. Under the watchful eye of the teacher, they self-evaluate.

Inquiry-based learning is valued by teachers because it tends to encourage students to be actively engaged with their learning. The teacher releases some control over the lesson, helping students create their own “aha” discovery moments.

Writing for the online resource Ellipsis Education, curriculum specialists Stephanie Bennett and Kate Baird highlight the work of professor John Hattie, a researcher in education who has been director of the Melbourne Educational Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, Australia, since March 2011. He holds a PhD from the University of Toronto.

Dr. Hattie became known to a wider public with his two books Visible Learning and Visible Learning for Teachers, the result of 15 years of research about what works best for teaching and learning in classrooms at all levels. He has been called possibly the world’s most influential education academic.

Hattie’s philosophy clearly shows his belief in the value of the implementation of a variety of approaches to teaching and learning, and he has not endorsed any one pedagogical approach.

He says his research has brought him to the conclusion that there is no one “right” way of teaching in order to effect learning, but insists that teachers adapt their teaching to activate learning for all students.

Which leaves us with the wisdom of a quote from Albert Einstein: “I never teach my pupils. I only attempt to provide the conditions in which they can learn.”

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]