South Burnaby’s hot water and space heating are one step closer to being powered by garbage.

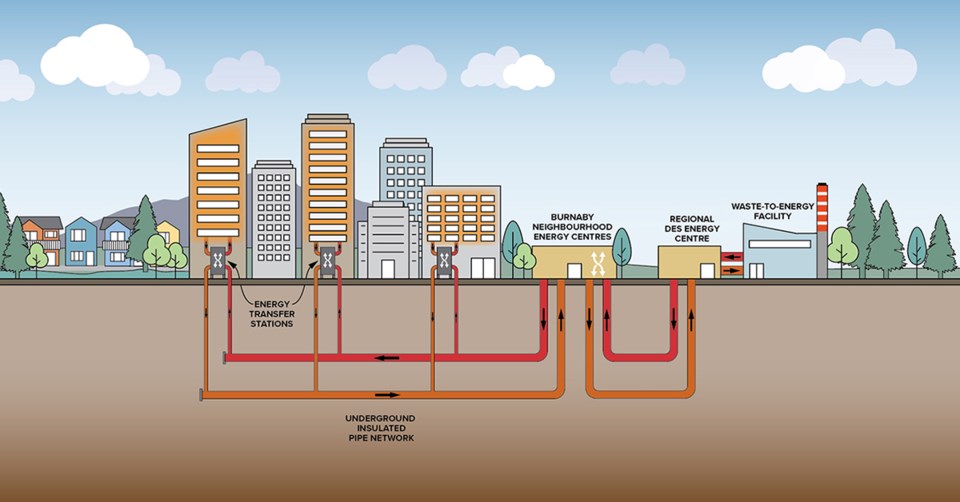

On March 27, council approved a new draft policy for a city-owned and operated “district energy utility” that will run a network of mechanical facilities and underground pipes, channeling heated water to buildings across South Burnaby.

The thermal energy will come from waste heat generated by Metro Vancouver’s Burnaby-based Waste-To-Energy Facility (WTEF), which burns garbage and turns it into electricity.

When the WTEF burns garbage, it creates steam, which is used to power a turbine that generates the electricity. With the new district energy system, more steam will be recovered to heat water, which will be pumped through regional pipes to neighbourhood energy centres in Metrotown and Edmonds.

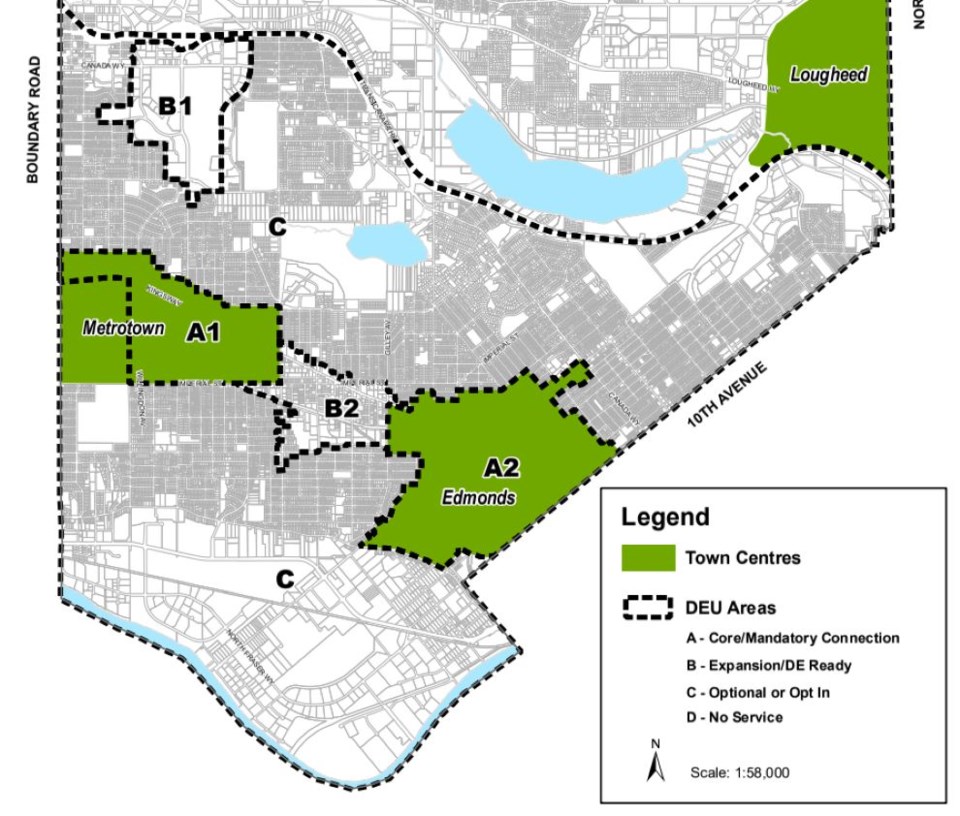

Those two neighbourhoods will be the primary service areas, as the town centres are expected to host almost half of the city’s new homes over the next 20 years, according to a staff report.

The neighbourhood energy centres, which will be about the size of “a small house” according to city staff, will distribute the heat from regional pipes to individual buildings and add heat using natural gas boilers when needed.

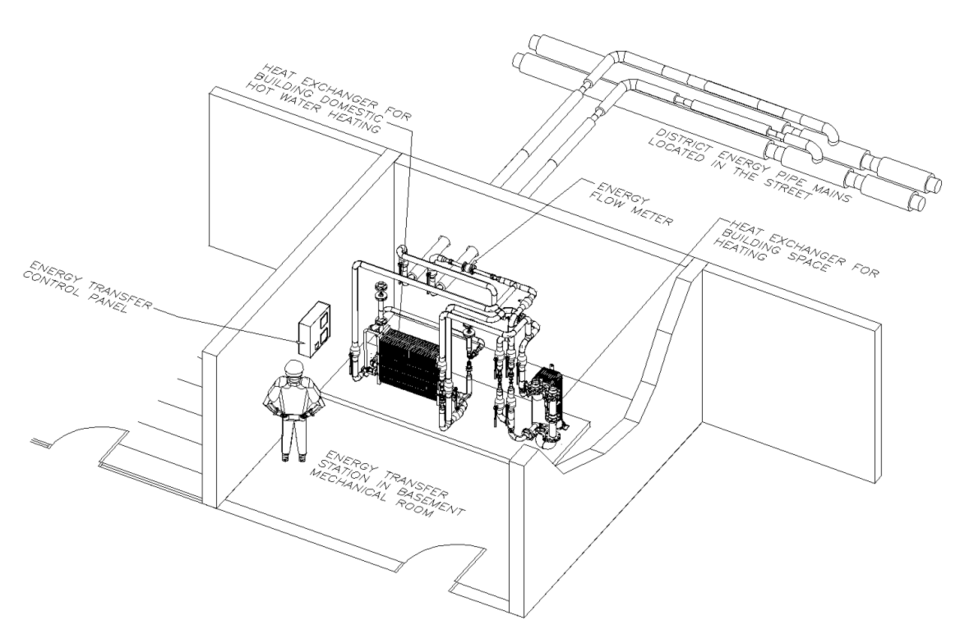

New residential buildings will swap their roof-based mechanical equipment for large refrigerator-sized energy transfer stations in the basement that exchange the thermal energy from the pipes to the building’s heating system.

The project is part of the city’s climate action goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – around 38 per cent of Burnaby’s carbon emissions come from buildings. The city expects to reduce about 82 per cent of CO2 equivalent annually when compared to business as usual, about 22,400 tonnes of CO2e.

Service connection to the utility is expected in 2026.

The system could heat up to 30,000 homes, mostly in multifamily complexes, once in full operation, according to the city.

The city estimates 92 per cent of the annual heating demand for Metrotown and 94 per cent of that for Edmonds can be supplied by heat from the WTEF.

Burnaby is planning future service expansion to the area between Willingdon Avenue, south of the Trans-Canada Highway and the Kingsway corridor between Metrotown and Edmonds.

The utility won’t service any neighbourhoods north of the Trans-Canada Highway.

The heat will be provided at or below market rates and would be rolled out over 25 years, with the majority of service provided between 2030 and 2040, according to staff at a development committee on March 8.

The main energy centre for the system was originally planned to neighbour the WTEF at Fraser Foreshore Park, however, due to recent public opposition to using land in the proposed area, the city’s general manager of lands and facilities James Lota said another spot will have to be found.

“We’re going to have to go back to the drawing board a bit and try and find another spot for it, but we think there’s a plan to get it there,” Lota said at the council meeting.

The city is also studying a boiler buy-back program to buy existing boilers to prepare buildings for when the utility is ready for service.

Burnaby’s district energy utility

Burnaby will initially be the owner and operator of the utility, as a branch of the engineering department.

The city plans to move it “eventually” to a local government corporation where the utility is owned by the city but operated “as a separate company, and the municipality’s role is limited to governance.”

Staff said North Vancouver’s Lonsdale Energy Company operates similarly, as does the Lulu Island Energy Company.

Burnaby is already home to various district heating systems, like the Burnaby Mountain district energy utility at SFU, BCIT, Solo District and Burnaby Central Secondary School, as well as a currently under-construction system for the Gilmore Place development, according to the staff report.

Staff say the district energy system will create local “green” jobs and be more reliable than traditional heating systems “as they keep operating during power outages and hydro or natural gas disruptions.”

It would also reduce the cost of heating equipment like boilers and take advantage of future affordable fuel sources, according to the report, and “free up roof tops” for developers to include other amenities by relocating mechanical equipment to a building’s basement.

Next steps include working with Metro Vancouver to get “cost competitive rates” and studying whether to provide cooling through the DES. Staff will also coordinate policies with the City of Vancouver for both sides of Boundary Road.

The policy is set to be officially adopted in fall 2023.

In-stream developments that haven’t reached a second reading by council will be required to follow the district energy policy.

New buildings of 100,000 square feet or more in Metrotown and Edmonds will be expected to connect to the utility, while existing buildings can opt in.

In 2022, Metro Vancouver announced its first district energy customer would be River District in South Vancouver.